“Journalism’s ‘both sides’ doctrine, a guiding principle for news coverage by American media outlets, died on Tuesday after a prolonged illness.” That’s the first line of an opinion piece by Erik Wemple at WaPo, and it certainly drew me in. I fear the obituary was a tad premature, but we can hope. However, I think there could be bigger issues at play here.

Wemple’s column focuses on the lawsuits filed by voting system companies Dominion and Smartmatic against Fox News. Fox, of course, aired many unsubstantiated claims that the voting machines flipped the 2020 election from Trump to Biden. Part of Fox’s defense is that they felt an obligation to report on “both sides” of a controversy. So the likes of Sidney Powell and Rudy Giuliani were given many, many hours on Fox News to make utterly unsupported claims of vote manipulation in the 2020 elections. That’s just reporting “both sides.”

“Battling a well-drafted complaint such as Dominion’s is typically a see-what-sticks affair. So in a motion filed Tuesday, lawyers for Fox News argue that the network ‘went straight to the newsmakers’ in pursuing its obligation to report on the allegations; that there is no requirement under the First Amendment for news organization to expose the ‘underlying falsity’ of such allegations; that Fox News has ‘complete protection’ to report on government proceedings; that Dominion fails to document ‘actual malice,’ the sky-high evidentiary standard required to prove a public figure committed defamation.”

“Actual malice” is taken from the Supreme Court’s ruling in a landmark 1964 case, New York Times v. Sullivan. When I was a journalism major at U. of Missouri (class of ’73) this case was ground into my head. It was seen as a huge victory for journalism and a protection for news companies from being nibbled to death by litigation.

You can find the basic facts of the case here. In 1964, the New York Times ran an advertisement soliciting donations to pay for a legal defense for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The ad criticized the Montgomery, Alabama, police department, and those criticisms contained some minor inaccuracies, including the number of times King had been arrested and what song protesters had sung. The Montgomery police commissioner, L.B. Sullivan, sued the Times in an Alabama county court, which ruled in favor of the commissioner. Under Alabama law, Sullivan only needed to prove that there were mistakes and that they likely harmed his reputation. The case then went to the Alabama Supreme Court and eventually SCOTUS.

Justice William Brennan wrote the opinion for a unanimous Supreme Court, and in that opinion he said that public officials “may not sue news media for slander or libel unless the injurious statement is made with actual malice or reckless disregard for the truth,” it says here. Public discussion of government officials and issues should be “uninhibited, robust and wide-open,” he said. The actual malice standard may protect falsehoods, but “erroneous statement is inevitable in free debate, and … it must be protected if the freedoms of expression are to have the ‘breathing space’ that they need to survive.”

Journalists certainly embraced this ruling, because there is no such thing as error-free news reporting. No matter how careful one is to get facts straight, there will always be sources that give inaccurate information — sometimes deliberately — and other just plain honest mistakes, especially when dealing with breaking news or very complex issues. New York Times v. Sullivan gave news companies some breathing room when reporting on public officials; they couldn’t be sued for inaccurate reporting or ads unless the official could prove actual malice, which requires proving that a statement was made “with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.” Again, this applies to statements made about public officials, not to anybody. However, later cases extended the Sullivan rule to apply to other newsworthy public figures.

Actual malice and reckless disregard for the truth are notoriously difficult to prove, and many argue that the Sullivan standard gives news companies way too much leeway in presenting deceptive reporting. It also allows ads for political candidates to just plain lie like rugs. Further, I personally think the actual malice and reckless disregard in much of Fox News programming is palpably obvious. If that can’t be proved in court, then there are no rules at all.

Fox is arguing that “reporting both sides” relieves them of the reckless disregard rule. We’re just inviting these newsmakers on and letting them express their opinions, Fox is arguing. We are under no obligation to fact check what they say. I don’t know if that one’s been tried before, but it shouldn’t be allowed to fly.

Back to Erik Wemple:

“In advancing its ‘both side’ defense, the motion argues that “coverage of the election-fraud allegations was often quite skeptical,” and cites broadcasts from hosts Laura Ingraham and Tucker Carlson (who notably challenged Powell to furnish evidence of her claims), as well as an interview by anchor Eric Shawn with a Dominion representative. Other Fox News personnel — including ‘Fox & Friends’ co-host Steve Doocy — rebutted or expressed doubts about the election-related conspiracy theories. Dominion, for its part, contends that this awareness actually deepens the network’s culpability. “While these handfuls of statements from a handful of people at Fox do not absolve Fox for its onslaught of defamatory statements about Dominion, they do demonstrate that Fox at a mininum [sic] recklessly disregarded, and really knew, the falsity of the lies its most popular on-air talent were repeatedly promoting about Dominion,” reads the company’s complaint.”

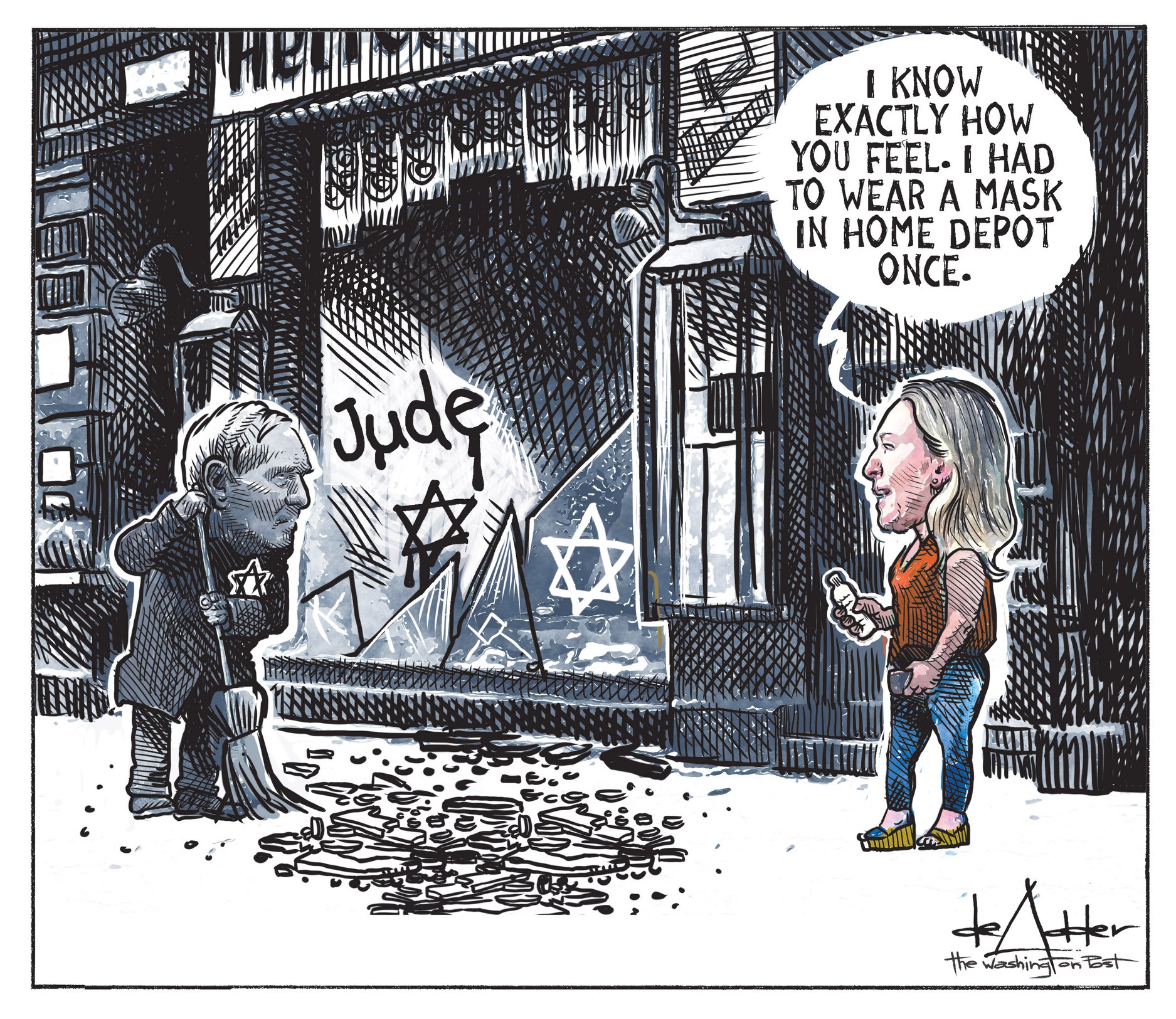

Oops. Wemple goes on to explain how media critics for decades have complained that “covering both sides” often means, for example, pitting a climate scientist and a climate change denier against each other in a studio while a moderator simply sits there and offers no editorial context. This may be entertaining — and it’s a lot cheaper than real investigative reporting — but it does the public a huge disservice by giving science and nonsense equal weight.

A lot of both siderism comes from media’s terror of being accused of bias. Way back in 2000, during the Bush v. Gore presidential election campaign, Paul Krugman famously wrote:

“One of the great jokes of American politics is the insistence by conservatives that the media have a liberal bias. The truth is that reporters have failed to call Mr. Bush to account on even the most outrageous misstatements, presumably for fear that they might be accused of partisanship. If a presidential candidate were to declare that the earth is flat, you would be sure to see a news analysis under the headline ”Shape of the Planet: Both Sides Have a Point.”’

Since Trump, at least part of the media is somewhat less constrained from calling out lies as lies. In 2000, it wasn’t yet allowed.

Erik Wemple again,

“Fox News is arguing that the Trump-Powell-Giuliani lies about the election constitute a ‘side.’ ‘There are two sides to every story,’ reads the network’s motion. ‘The press must remain free to cover both sides, or there will be a free press no more.'”

Are there really “two sides to every story”? I guestion that. Sometimes there might be multiple “sides” from the perspective of multiple factions. But sometimes there’s just one side, which is factuality. What really happened? What does the data tell us? The “two sides” argument tosses facts out the window and just measures two opposing perspectives, which could be entirely biased. That’s what journalism is supposed to root out and expose, not perpetrate.

But here’s what’s rich about the current state of the Sullivan case. Recently some conservative judges, including Justice Clarence Thomas, have been making noises about getting rid of the actual malice rule. W. Wat Hopkins writes at Washington Monthly about a D.C. Circuit panel judge who wrote a dissenting opinion calling for an end to the actual malice rule. Why? Because it protects liberals.

“Silberman’s disdain for the actual malice rule was directly tied to its protection of what he dubbed liberal media who, he wrote, ‘manufacture[] scandals involving political conservatives.’ Finding their bias against the Republican Party shocking, he wrote, ‘The ideological homogeneity in the media—or in the channels of information distribution—risks repressing certain ideas from the public consciousness just as surely as if access were restricted by the government.’ He specifically identified as culprits The Washington Post, The New York Times, and the news sections of The Wall Street Journal. (Silberman approves of the Journal’s editorial stance.) He declared that ‘a biased press can distort the marketplace. And when the media has proven its [sic] willingness – if not eagerness – to so distort, it is a profound mistake to stand by unjustified legal rules that serve only to enhance the press’ power.'”

To which I say, okay. Do we want to allow candidates for public office to sue a television news station when it runs their opponents’ political ads making false accusations about them? That would put pretty much all Republican Party campaign ads in 2020 off the air. Yes, it would cancel some Democrats’ ads too, but not all of them, and probably not most of them.

And do we want to shut down the ability of Fox News to put any wackjob in front of a camera to lie about Democrats with no fact checking whatsoever? Maybe it’s time.

Once again, righties, be careful what you wish for.