[Update: Macranger ought to have read my post all the way through before he linked to it. I don’t say what he seems to think I said.]

My impression is that yesterday’s antiwar protests got more news coverage than the big march around the White House in September 2005. And this is true in spite of the fact that the crowd showing up for the 2005 march was much bigger, estimated — conservatively — as between 100,000 and 200,000. From news stories (which, I realize, always lowball these things) it seems the turnout in Washington yesterday fell short of 100,000. Although nobody really knows.

More news coverage is not necessarily better news coverage. Take a look at the Washington Post story by Michael Ruane and Fredrick Kunkle:

A raucous and colorful multitude of protesters, led by some of the aging activists of the past, staged a series of rallies and a march on the Capitol yesterday to demand that the United States end its war in Iraq.

Under a blue sky with a pale midday moon, tens of thousands of people angry about the war and other policies of the Bush administration danced, sang, shouted and chanted their opposition.

They came from across the country and across the activist spectrum, with a wide array of grievances. Many seemed to be under 30, but there were others who said they had been at the famed war protests of the 1960s and ’70s.

Note especially —

Among the celebrities who appeared was Jane Fonda, the 69-year-old actress and activist who was criticized for sympathizing with the North Vietnamese during the Vietnam War. She told the crowd that this was the first time she had spoken at an antiwar rally in 34 years.

“I’ve been afraid that because of the lies that have been and continue to be spread about me and that war, that they would be used to hurt this new antiwar movement,” she told the crowd. “But silence is no longer an option.”

Dear Jane: Get a blog.

I didn’t watch television yesterday but I take it the television news was All About Jane. I don’t know that this hurt the cause — people still enflamed about Jane are likely to be Bush supporters, anyway — but I can’t see that it helped, either.

At the Agonist, Sean-Paul Kelly criticized Jane’s attendance and got slammed for it in comments. But I’m with Sean-Paul here. Public protests are about action in service to a cause. Whether Jane Fonda has a right to protest — of course she does — it not the point. Jane Fonda has a right to smear herself with molasses and sit on an anthill, but just because one has a right to do something doesn’t make it smart.

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again — good public protests are good public relations. Protest movements of the past were effective when they called attention to an issue and gained public sympathy for it. And the secret to doing this is what I call the “bigger asshole” rule — protests work when they make the protestees look like bigger assholes than the protesters. Martin Luther King’s marches made white racists look like assholes. Gandhi made the whole bleeping British Empire look like assholes.

The Vietnam-era antiwar protesters, on the other hand, more often than not shot themselves in the foot by coming across as bigger assholes than Richard Nixon and other Powers That Were. Steve Gilliard has a good post up today reaffirming my opinion that the Vietnam antiwar movement did little or nothing to actually stop the war.

And, m’dears, the point is to stop the war. It is not about expressing yourself, feeling good about yourself, or even “speaking truth to power.” It is about stopping the war. Action that does not advance the cause of stopping the war is not worth doing.

In fact, I wonder if these “raucous and colorful” public displays might be trivializing a deadly serious issue.

I disagree with protest defenders that any street protest is better than no street protest. Believe me; no street protesting is preferable to stupid street protesting. I have seen this with my own eyes. And these days there are plenty of ways to speak out against the war than to carry oversized puppets down a street.

That said, based on this video, the protest in Washington yesterday seemed a perfectly respectable protest, although not notably different from other protests of recent years. Some politicians actually turned out for this one, which was not true in September 2005. This is progress.

IRAQ WAR PROTEST – JAN. 27, 2007

John at AMERICAblog had mostly positive comments, also.

But will public protests like this change any minds that haven’t already been changed by events? I don’t see how.

That said, I want to respond to this post by Rick Moran of Right Wing Nut House:

The May Day protest in Washington, D.C. sought to shut down the government. Some 50,000 hard core demonstrators would block the streets and intersections while putting up human barricades in front of federal offices. How exactly this would stop the war was kind of fuzzy. No matter. Nixon was ready with the army and National Guard and in the largest mass arrest in US history, clogged the jails of Washington with 10,000 kids.

Where are the clogged jails today? As I watch the demonstration on the mall today (much smaller than those in the past) I am thinking of the massive gulf between the self absorbed hodge podge of anti-globalist, pro-feminist, anti-capitalist, pro-abortion anti-war fruitcakes cheering on speakers lobbying for Palestinians, Katrina aid, and other causes not related to the war and the committed, determined bunch of kids who put their hides on the line, filling up the jails of dozens of cities, risking the billy clubs and tear gas of the police to stop what they saw as an unjust war.

The netnuts are fond of calling those of us who support the mission in Iraq chickenhawks. What do you call someone who sits on their ass in front of a keyboard, railing against the President, claiming that the United States is falling into a dictatorship, and writing about how awful this war is and yet refuses to practice the kinds of civil disobedience that their fathers and mothers used to actually bring the Viet Nam war to an end?

I call them what they are; rank cowards. There should be a million people on the mall today. Instead, there might be 50,000. Today’s antiwar left talks big but cowers in the corner. I have often written about how unserious the left is about what they believe. The reason is on the mall today. If they really thought that the United States was on the verge of becoming a dictatorship are you seriously trying to tell me that any patriotic American wouldn’t do everything in their power to prevent it rather than mouth idiotic platitudes and self serving bromides?

He as much as admits of the May Day (1971) protest, “How exactly this would stop the war was kind of fuzzy.” If I actually believed that getting myself arrested by blocking the door to the FBI building would help end the war, then I believe I would do it. But since I don’t see how such an arrest would make a damn bit of difference, except maybe get my glorious little self in the newspapers (and “no fly” lists), why would I do that? And why am I a “coward” for not doing it?

I haven’t yet smeared myself with molasses and sat on an anthill, either. Does that make me a coward? Or not crazy?

The other part of this post I want to respond to is his accusation that the antiwar left is “not serious.” He speaks of “the self absorbed hodge podge of anti-globalist, pro-feminist, anti-capitalist, pro-abortion anti-war fruitcakes cheering on speakers lobbying for Palestinians, Katrina aid, and other causes not related to the war,” and wonders why more of us don’t show up. Well, son, a lot of the reason more people don’t show up is in fact “the self absorbed hodge podge of anti-globalist, pro-feminist, anti-capitalist, pro-abortion anti-war fruitcakes cheering on speakers lobbying for Palestinians, Katrina aid, and other causes not related to the war.” It is damn frustrating for those of us serious about ending the war to spend the time and money to go somewhere for a protest and find our efforts diluted by the vocational protest crowd.

Moran is making the same error that Gary Kamiya made; he assumes that a “real” antiwar movement has to look and act just like the Vietnam-era antiwar movement. I say again, that movement failed. Why should we be emulating it today?

Moreover, claiming the left isn’t “serious” about ending the war because we’re not all engaging in pointless publicity stunts rather ignores what we are doing, and what we have accomplished. Remember the midterm elections?

Please, Rick Moran, get serious.

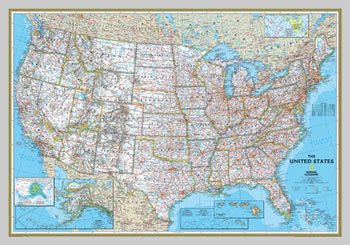

As for Mr. Moran’s question about people opposed to the war — “Where is everybody?” — I believe they’re here: