Easter is a bipolar holy day, in which the faithful commemorate Jesus’ transcendence from fleshly corruption and death with pagan fertility symbols — bunnies and eggs. That’s genuinely weird, if you think about it.

The Venerable Bede, a sixth-century theologian, was the one who claimed the name Easter came from an Anglo-Saxon goddess of spring, Eostre, who was associated with eggs and bunnies. However, I understand there is no earlier record of an Anglo-Saxon goddess named Eostre, and some people think ol’ Bede made her up.

The Venerable Bede, a sixth-century theologian, was the one who claimed the name Easter came from an Anglo-Saxon goddess of spring, Eostre, who was associated with eggs and bunnies. However, I understand there is no earlier record of an Anglo-Saxon goddess named Eostre, and some people think ol’ Bede made her up.

Regarding Jesus — Historian Paula Fredriksen argued (persuasively, IMO) that the historic Jesus was a devout Jew who did not claim to be a Messiah. I’ve come to agree with Thomas Jefferson that Jesus’ life story is more compelling without the miracles, and with Richard Rubenstein that the deification of Jesus is an unfortunate distraction from his remarkable teachings.

But that’s me. For those who have faith in the Resurrection — happy Easter.

Which takes me to the topic of today’s sermon — “Religion: What Is It Good For?”

This essay by James Randerson asks the question, “Would we be better off without religion?” I agree with Randerson that many of the supposed benefits of religion are questionable. For example, it’s true that religion inspired much great art and music, but there’s plenty of great art and music inspired by other stuff.

Randerson quotes the Baroness Julia Neuberger: “In my view if we didn’t have religion, we would be more selfish, self interested, certain and cruel.” So what about the hordes of religious people who are selfish, self interested, certain and cruel? It seems to me that for every Mohandas Gandhi, Albert Schweitzer, or Aung San Suu Kyi there must be thousands of selfish, self-interested, certain and cruel little creeps like Ralph Reed or Pat Robertson, not to mention some standout evildoers like Torquemada or Osama bin Laden.

I think the real basis of most moral behavior is good socialization and the ability to feel empathy for others. A religious sociopath is not cured by his faith. Rather, religion becomes the context, and excuse, for his sociopathy; cruelty is OK if you’re doing it for God.

It’s assumed that religion causes people to be virtuous, but philosophical Taoism says it’s the other way around — religion is what you fall back on when you lose virtue (see, for example, verse 38 of the Tao Teh Ching). Religion in ancient China was more about ceremony and ritual than it was about faith, but I don’t believe the old Taoists would have had much use for faith, either. Anyway, I question whether morality and ethics developed from religion, or whether they developed out of some shift in human consciousness during the Axial Age that subsequently reformed religion.

Put another way, did religion cause our species to (mostly) transcend barbarism, or did we transcend barbarism through other means and then drag religion along after us?

“The real question,” Mr. Randerson says, “is whether the best of humanity is already inside us or whether it needs faith to bring it out.” That’s a good question. I think faith does bring out the best in some people, but it seems to inspire the worst in others.

In America, it always seems that the people who blather on most about “God’s love” and “Christian values” are the same ones who promote homophobia and harass women outside abortion clinics. I can’t blame the non-religious for being distrustful of religion. But I don’t think religion, including Christianity, by itself is to blame. If you look at the long history of Christianity, you might notice a pattern — Christianity tends to get ugly when it becomes The Establishment. The worst things done in the name of Jesus were truly done to defend or strengthen a political or social authority in which religious institutions had become inextricably embedded. Grand Inquisitors like Torquemada were working on behalf of the monarchy as much as for the Church.

In spite of official (not always enforced) separation of church and state, Christianity is The Establishment in America. Particularly in conservative parts of the country, the large evangelical and pentecostal denominations are accustomed to being the dominant, privileged tribe. When Christians are denied use of government resources for the purpose of maintaining their dominance, or when Christianity is not given special deference or privilege above other religions, it is perceived by some Christians as oppression. To non-Christians, this whining about the oppression of Christians is just plain irrational. It’s like a whale complaining that a minnow is taking up too much ocean space.

In spite of official (not always enforced) separation of church and state, Christianity is The Establishment in America. Particularly in conservative parts of the country, the large evangelical and pentecostal denominations are accustomed to being the dominant, privileged tribe. When Christians are denied use of government resources for the purpose of maintaining their dominance, or when Christianity is not given special deference or privilege above other religions, it is perceived by some Christians as oppression. To non-Christians, this whining about the oppression of Christians is just plain irrational. It’s like a whale complaining that a minnow is taking up too much ocean space.

I think much of what this essay by Simon Barrow says about the established church in Britain applies to the U.S. also.

I think the reason for mostly conservative Christians feeling discriminated against is this. They have grown up accustomed to the idea that Britain is a “Christian country” and that Christian institutions, symbols, representatives and (what they take to be) Christian values have a fixed place at the centre of our national culture.

Others now point out that practising Christianity is a minority pursuit in a multi-conviction society. They say that, in any case, Christians are a mixed bunch who disagree among themselves pretty vociferously. So privileging one outlook (particularly, one faith) is no longer tenable.

This means that Christians no longer automatically set the ground rules. They have to negotiate with others – and their Christian identity is not necessarily the ground on which this will happen. … to those who have been used to their cherished ideas holding sway in the public square, the removal of the ground from under their feet appears pretty threatening.

I think that’s exactly right, although I have no idea how to get the whiners to understand this. Simon Barrow calls for “reasoned argument.” Yeah, right. Good luck with that, dude.

But then Barrow goes on to say this —

For my part, I’d like to argue that Christians are entirely on the wrong track trying to defend the vestiges of a “Christian nation”. The gospel message, long submerged by the churches’ collusion with the state, is one of radical equality, a reversal of social norms, even. It argues that the first shall be last and the last first.

For this reason, Christians should not be out to defend their institutional privileges, let alone denying equal rights. On the contrary, they have an opportunity to embrace (rather than fear) a new status as a creative minority within a society which, helpfully, tries to offer a place for all. That fairness is something worth arguing for. But it cannot coexist with privilege.

E.J. Dionne wrote something along these same lines last week.

As for me, Christianity is more a call to rebellion than an insistence on narrow conformity, more a challenge than a set of certainties.

In ” The Last Week,” their book about Christ’s final days on Earth, Marcus J. Borg and John Dominic Crossan, distinguished liberal scriptural scholars, write: “He attracted a following and took his movement to Jerusalem at the season of Passover. There he challenged the authorities with public acts and public debates. All this was his passion, what he was passionate about: God and the Kingdom of God, God and God’s passion for justice. Jesus’ passion got him killed.”

This speaks to why a mortal Jesus is a more interesting, and compelling, figure to me than a divine one. Here was a man who, after a dark night of the soul in the wilderness, realized something wonderful. And he went out and tried to explain this something to people, and maybe his followers understood him, and maybe they didn’t. Maybe his words are pretty much faithfully recorded in the synoptic gospels, and maybe much of what he said got scrambled. And much of institutional Christianity seems unconcerned about what Jesus was trying to teach. Instead, Jesus became a blank slate onto which generations of saints and sociopaths projected their deepest desires for transcendence or dominance.

(And might I add that I realize there may not have been a historical Jesus; maybe his story is a fabrication. You can say the same thing for the Buddha, and in a sense it doesn’t matter. What’s important are the teachings. But especially in Jesus’ case it makes more sense to assume the teachings originated with some guy whose followers revered him and attempted to preserve what he taught. If later generations of people projected miracles and eventually godhood onto the guy’s memory doesn’t mean Jesus never existed.)

Thus, you get people like Rep. Lynn Westmoreland (R-Georgia), who supported a bill to display the Ten Commandments in the U.S. House chamber, but could only name three commandments (sort of) when challenged to do so. This suggests the congressman cares about the 10Cs as a symbol of something, not for what they actually say. And I think what they’ve come to be symbolic of is more about worldly power and authority than about God.

And this, children, is why Christianity is bleeped up.

Let’s go back to what religion is good for. If Jesus’ message was primarily about radical equality and justice, then we’re still not finding something unique to religion. Although radical equality was Out There in the first century, today lots of non-religious people promote it or something like it.

So we come to religion as comfort. Faith, and reliance on a higher power, is a great comfort to people who are troubled and afraid. One might argue that religion in this sense is just an emotional crutch. And if the higher power is imaginary, it’s a placebo.

Belief in a higher power that looks out for his followers also gave us George W. Bush, who has mistaken his own almighty ego for God, with disastrous consequences.

There is confusion, I think, about what religion actually is. These days people use the word faith as a synonym for religion, and I don’t think that’s accurate for many religions. In the West, when people want to learn about a foreign religion the first thing they ask is “What do the followers of this religion believe.” When you are dealing with most of the Asian religions, that’s the wrong question. You can memorize the entire panoply of Hindu gods, for example, and still not understand Hinduism. The point is not to believe this or that, but to realize the true nature of everything that is, including yourself. In this sense, belief in gods and myths is not the point of the religion, but rather are means to an end that transcends gods and myths.

Google “etymology religion” and you get all manner of answers. The most common answer is that it comes from the Latin word religio, meaning “to bind.” But another source says it comes from relegere, “to treat carefully.” So it could refer to a discipline, or a submission to rules, or binding to God. It might refer to something that needs your attention and careful treatment. It could mean a lot of things that may or may not involve beliefs.

Jesus went on and on about the Kingdom of Heaven and how people should be seeking it. “The kingdom of heaven is like treasure hidden in a field, which a man found and covered up. Then in his joy he goes and sells all that he has and buys that field. [Matthew 13:44, English Standard Version]” Much church dogma claims this Kingdom is something that will happen in the future, or perhaps is where you go when you die, but I think an unprejudiced reading of the gospels suggests Jesus taught the Kingdom is here-and-now; we’re just not seeing it. I don’t think Jesus wanted people merely to have faith in it; he wanted people to see it.

Finally we stumble onto what religions is good for. I say it is a means to the realization of something dangling just outside the scope of conceptual knowledge, something unreachable by logic or cognition. And that something, when seen, changes everything; it transforms how you understand yourself and everything else. In human history teachers and mystics from myriad religious traditions have had transformative realizations. And all the gods and rituals and beliefs and dogmas of all the religions of the earth are just provisional means for achieving this transformation. As the Buddha said, once you’ve reached the other shore you don’t need the boat any more.

But religious institutions, particularly powerful ones, in time become more interested in maintaining power than in religion. Then people who are selfish, self interested, certain and cruel come along and put religion to their own ego-driven uses. This happens in all religions; Christianity is no more or less susceptible than any other, I don’t think.

Maybe someday conservative Christians will stop trying preserve the vestiges of a “Christian nation.” When they do, maybe they’ll rediscover Jesus. That would be nice.

-

Therefore, the full-grown man sets his heart upon

-

the substance rather than the husk;

-

Upon the fruit rather than the flower.

Truly, he prefers what is within to what is without. — Tao Teh Ching

~~~~~~~~~

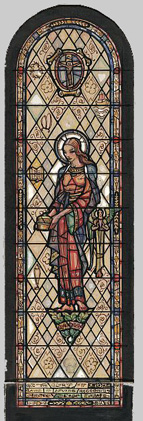

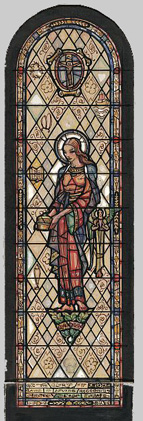

I posted the photo of Grace Coolidge because it cheers me to think there was once a First Lady who kept a pet raccoon in the White House. I don’t think much of Calvin, but I believe I would have liked Grace. The lady in the stained glass window at the top of the post is Mary Magdalene.

The Venerable Bede, a sixth-century theologian, was the one who claimed the name Easter came from an Anglo-Saxon goddess of spring,

The Venerable Bede, a sixth-century theologian, was the one who claimed the name Easter came from an Anglo-Saxon goddess of spring,  In spite of official (not always enforced) separation of church and state, Christianity is The Establishment in America. Particularly in conservative parts of the country, the large evangelical and pentecostal denominations are accustomed to being the dominant, privileged tribe. When Christians are denied use of government resources for the purpose of maintaining their dominance, or when Christianity is not given special deference or privilege above other religions, it is perceived by some Christians as oppression. To non-Christians, this whining about the oppression of Christians is just plain irrational. It’s like a whale complaining that a minnow is taking up too much ocean space.

In spite of official (not always enforced) separation of church and state, Christianity is The Establishment in America. Particularly in conservative parts of the country, the large evangelical and pentecostal denominations are accustomed to being the dominant, privileged tribe. When Christians are denied use of government resources for the purpose of maintaining their dominance, or when Christianity is not given special deference or privilege above other religions, it is perceived by some Christians as oppression. To non-Christians, this whining about the oppression of Christians is just plain irrational. It’s like a whale complaining that a minnow is taking up too much ocean space.