I think it’s time to remind people that in the early Red Scares, post-Bolshevik Revolution, communism didn’t represent “totalitarianism” but “anarchy.” In early anti-communist literature, “communist” and “anarchist” are used as synonyms. You see this in this 1920 essay by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, “The Case Against the Reds.” The case Palmer makes is not that Communism would create an oppressive totalitarian state but that it would destroy all authority and let lawlessness and crime run rampant.

Of course, as government calling themselves “communist” became ruthlessly dictatorial, peoples’ ideas about communism shifted. But Marx’s original vision was of a society without government where free people, unencumbered by class distinctions, would communally and democratically make decisions together. Yeah, it didn’t work.

I thought of this after reading the comment thread attached to this post at Reason. The blogger dutifully criticizes Sen. Richard Shelby for holding up nominations just to secure pork for Alabama. But most of the commenters don’t see it that way. Example:

Yes,Team Blue is in power.They hold the executive and legislative branches of government.When Team Red is trying to constrain state power I’m rooting for them.

Exactly how Shelby’s act of grandstanding isn’t “state power” also eludes me.

Anyway, some of the commenters refer to themselves as “an-cap,” which I take it stands for “anarchist-capitalist.” The an-caps are opposed to all government, period. When one person issued a challenge, “Who enforces your contracts,” an an-cap had a ready answer — a link to this document, “Privatizing the Adjudication of Disputes,” in which a couple of whackjobs seriously argue in favor of a private, for-profit criminal justice system.

Just read it. It’s one of the most jaw-dropping-ridiculous things I’ve ever seen. The bozos authors criticize the “near-monopoly of law that most governments possess,” and argue in favor of putting “public” courts out of business.

Here’s a radical idea of returning to the good old days:

Legal centralists posit that legal systems must govern everyone to function at all. If lawbreakers could simply drop out of the system, law could hardly protect us from their misdeeds. And yet, history contains many instances of pluralistic legal systems in which multiple sources of law existed in one geographic region. These were much more sophisticated than primitive law. In medieval Europe, for example, canon law, royal law, feudal law, manorial law, mercantile law, and urban law co-existed; none was automatically supreme over the others. Naturally, some jurisdictional conflicts occurred. But this system of concurrent jurisdiction overlapped with a period of economic development (c.1050-1250), not a period of chaos and impoverishment. Apparently these diverse systems did what Thomas Hobbes declared impossible: They created social order and peace in the absence of a distinct, supreme sovereign.

Look at the time peoriod — they are talking about the glory days of European feudalism, folks. I guess you could say there was social order and peace, but there was also serfdom. The real thing, not the kind Friedrich von Hayek wrote about. If you were one of the privileged few born into the aristocracy, I guess life probably was pretty sweet. But otherwise, Hobbes was right — for serfs, life was nasty, brutish, and short.

Here’s the conclusion of the paper:

For arbitration to live up to its full potential, however, government has to stop holding it back. Public courts should, as a matter of policy, respect contracts that specify final and binding arbitration. Legislatures should abolish laws that hamper ostracism, boycott, and other non-violent private enforcement methods. These small changes would make private courts much more attractive than they already are – and go a long way toward putting the public courts out of business.

“Private enforcement methods.” It sounds so banal. As in sending around that nice Vinnie “the Nickle” De Luca to make you an offer you can’t refuse. Before long a small coterie of people with means will have a monopoly on “private enforcement.” That’s not at all what the authors of the paper intend, of course, but it’s how their ideas would turn out in the real world.

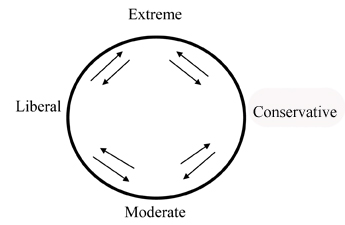

The early Marxist ideal was to eliminate private property, and utopia would follow. The an-caps think that by making everything private, utopia will follow. Both groups value human freedom and desire an end to oppression. Put into practice, seems to me both inevitably lead to the utter subjugation of most people under the rule of a powerful few. Extremists may go around opposite sides of the circle, and their rhetoric and ideals may be utterly different, but sooner or later they end up in the same place.

This is grossly over-simple, but it’s how politics works. Extremist ideas all end up in about the same place, whether they originated on the Left or the Right. That’s because ideas that aren’t based in reality and real human nature generally pave the way for oppression and, eventually, totalitarianism. Anarchism has never brought about greater freedom; it just sets up conditions for some sort of Strong Man, whether tribal warlords or a national dictator, to step into the power vacuum.

All we can hope is that “an-cap” ideas never get put into practice.

For another perspective on Shelby et al., see Krugman.