I’ve linked to this in the past, but it’s still good — “The Long Funeral” by John Homans, published in New York magazine in 2006.

New Yorkers tended to want to keep 9/11 (“it happened to usâ€) for their own, but no one believed that could happen. The grief culture this country has lived in for the past five years began in those spontaneous shrines, but it didn’t end there. Before the week was out, many different interests had moved in to stake their claims on its meaning.

As an event, 9/11 was a perfect entry point into the softness and indulgence and inwardness that mass media are most comfortable exploiting. In this, it was clearly part of what came before, the high-rated bathos of the deaths of Princess Di and JFK Jr. (or more recently, for that matter, the cat stuck in the wall of a West Village bakery), the media’s hunger for strong emotion coupled with its ability to make huge numbers of people think the same thing at the same time. The journalistic necessity of putting faces on the story minted a huge new class of celebrities, dead and alive. Jokes, of course, could be told about Princess Di and JFK Jr. But the grief culture that had just been born imposed its own form of correctness. The circles of loss and victimhood created a new etiquette—who could speak first, what could be said.

Paul Krugman writes today,

What happened after 9/11 — and I think even people on the right know this, whether they admit it or not — was deeply shameful. The atrocity should have been a unifying event, but instead it became a wedge issue. Fake heroes like Bernie Kerik, Rudy Giuliani, and, yes, George W. Bush raced to cash in on the horror. And then the attack was used to justify an unrelated war the neocons wanted to fight, for all the wrong reasons.

Back to Homans in 2006 —

Bush and his administration quickly swooped down to scoop up the largest part of the 9/11 legacy. The justified fear and rage and woundedness and sense of victimhood infantilized our political culture. The daddy state was born, with attendant sky-high approval ratings. And for many, the scale of the provocation seemed to demand similarly spectacular responses—a specious tactical argument, based as it was on the emotional power of 9/11, rather than any rearrangement of strategic realities.

Of course, the marriage of the ultimate baby-down-a-well media spectacle with good old American foreign-policy adventurism was brokered by Karl Rove, who decreed that George Bush would become a war president, indefinitely.

Krugman, today:

The memory of 9/11 has been irrevocably poisoned; it has become an occasion for shame. And in its heart, the nation knows it.

Homans 2006 —

The memory of 9/11 continues to stoke a weepy sense of American victimhood, and victimhood, as used by both left and right, is a powerful political force. As the dog whisperer can tell you, strength and woundedness together are a dangerous combination. Now, 9/11 has allowed American victim politics to be writ larger than ever, across the globe. When someone from Tulsa, for example, says, “It’s important to remember 9/11 every day,†what he means is, “We were attacked, we are the aggrieved victims, we are justified.†But if we were victims then, we are less so now. This distorted sense of American weakness is weirdly mirrored in the woundedness and shame that motivate our adversaries. In our current tragicomedy of Daddy-knows-best, it’s a national neurosis, a perpetual childhood. (With its 9/11 truth-conspiracy theories, the far left has its own infantile daddy complex, except in that version, the daddies are the source of all evil.) No doubt, there are real enemies, Islamist and otherwise, more than ever (although the cure—the Iraq war—has inarguably made the disease worse). But the spectacular scope of 9/11, its psychic power, continues to distort America’s relationships. It will take years for the country to again understand its place in the world.

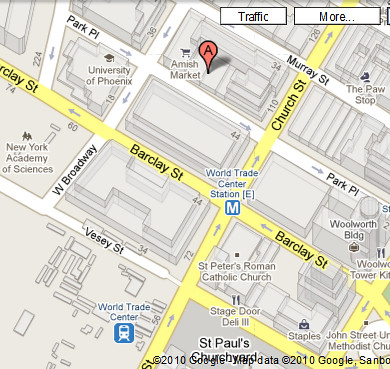

As you can imagine, righties are having screaming fits over what Krugman wrote today. But as Homans wrote five years ago, there’s a common feeling among New Yorkers that this profound and intimate experience was ripped away from us and exploited and re-interpreted by others who weren’t part of it, who weren’t even here.

New Yorkers responded to the disaster with grace and courage. It still inspires me that so many were able to escape, and they did so helping each other, often strangers, to get away. People were afraid, but no one was trampled to death in the WTC stairwells or on the streets. The courage of the firefighter and other responders also is not diminished.

I even give Rudy Giuliani credit for holding the city together emotionally in the hours and days immediately after the attacks, especially while the “President” was still flapping around aimlessly in Air Force One or hiding in the White House. But the fact remains that his own policies and decisions were partly responsible for the deaths of many firefighters that day. And since then he’s taken self-glorification to Olympic, and sickening, heights. But for a while, he found the right words when the city needed the right words.

But I utterly disagree with Jeffrey Goldberg —

Self-criticism is necessary, even indispensable, for democracy to work. But this decade-long drama began with the unprovoked murder of 3,000 people, simply because they were American, or happened to be located in proximity to Americans. It is important to get our categories straight: The profound moral failures of the age of 9/11 belong to the murderers of al Qaeda, and those (especially in certain corners of the Muslim clerisy, along with a handful of bien-pensant Western intellectuals) who abet them, and excuse their actions. The mistakes we made were sometimes terrible (and sometimes, as at Abu Ghraib and in the CIA’s torture rooms, criminal) but they came about in reaction to a crime without precedent.

Reaction, yes. That’s the whole problem. We reacted. We didn’t respond, we reacted. I wrote awhile back,

A wise person pointed out to me once that there’s a difference between reacting and responding. As it says here, reacting is a reflex, like a knee-jerk. Reacting is nearly always triggered by emotions — attraction or aversion — and is about making oneself feel better. Responding, on the other hand, is a thought-out and dispassionate action that is primarily about solving a problem.

Another article I had linked to in the paragraph above has since disappeared, but the point is that in reacting, we gave more power to al Qaeda. We let them goad us into reacting with the worst in ourselves. Al Qaeda didn’t torture prisoners at Abu Ghraib or Guantanamo; we did. Al Qaeda didn’t play fast and loose with our 4th Amendment rights; we did. Al Qaeda sure as hell didn’t force us to start a pointless war in Iraq.

Basically, what Goldberg is saying is that lynch mobs are blameless because, you know, they’re just reacting to something outrageous. But we Americans like to pretend, at least, we’re better than that. I guess not.

Executive summary: In the spring and summer of 2001, the Bush Administration was given a lot more intelligence about bin Laden’s pending terrorist attack than has been brought to public attention so far. The infamous August 6 “Bin Laden Determined to Strike in U.S.†brief we do know about was only one of a string of briefs that provided much more intelligence about bin Laden’s intentions. The Bushies ignored this largely because the neocons who had taken over the Pentagon believed that bin Laden was trying to create a diversion from the real evil being concocted by Saddam Hussein. Seriously. Middle East experts who tried to explain that it was absurd to think that fundamentalist bin Laden and secularist Hussein were in cahoots were simply ignored. Although the Bushies did not know the time, place, and specific targets of the pending attack, it’s not unreasonable to think that if they had been on higher alert the 9/11 attacks could have been stopped.

Executive summary: In the spring and summer of 2001, the Bush Administration was given a lot more intelligence about bin Laden’s pending terrorist attack than has been brought to public attention so far. The infamous August 6 “Bin Laden Determined to Strike in U.S.†brief we do know about was only one of a string of briefs that provided much more intelligence about bin Laden’s intentions. The Bushies ignored this largely because the neocons who had taken over the Pentagon believed that bin Laden was trying to create a diversion from the real evil being concocted by Saddam Hussein. Seriously. Middle East experts who tried to explain that it was absurd to think that fundamentalist bin Laden and secularist Hussein were in cahoots were simply ignored. Although the Bushies did not know the time, place, and specific targets of the pending attack, it’s not unreasonable to think that if they had been on higher alert the 9/11 attacks could have been stopped.