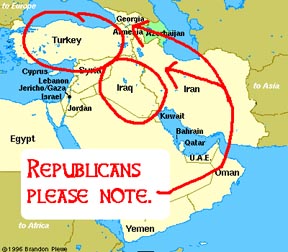

I’ve been thinking about comments to the last post regarding war powers and presidents. Seems to me that if we ever take our country back from the wingnuts we’ve got to revisit the issue of war powers.

First, we need to rethink war itself. How do we distinguish a “state of war” from a “military action”? Is the U.S. in a state of war every time any American soldier somewhere in the world is under fire? Is the U.S. in a state of war when, for example, American military personnel take part in a NATO action such Kosovo?

You might remember this CBS interview of Condi Rice by Wyatt Andrews (November 11, 2005):

QUESTION: Madame Secretary, thanks for joining us. I want to start with the Congressional investigation into “exaggerated intelligence.” Why the counter-offensive? Mr. Hadley was out yesterday. The President seems to be out today. Why the counter-offensive?

SECRETARY RICE: Well, this is simply a matter of reminding people of what the intelligence said about Iraqi weapons of mass destruction, about the fact that for 12 years the United Nations passed Security Council resolution after Security Council resolution calling on Saddam Hussein to cooperate about his weapons of mass destruction, about report after report, after report that talked about the absence of any data on what he had done with these weapons of mass destruction and calling on him to make a full account, the fact that we went to war in 1998 because of concerns about his weapons of mass destruction.

So Saddam Hussein and weapons of mass destruction were linked. The Oil-for-Food program —

QUESTION: Madame Secretary, I don’t mean to interrupt, but you said ’98. Did you mean ’91?

SECRETARY RICE: No, I mean in ’98 when there was —

QUESTION: You mean the cruise missile —

SECRETARY RICE: That’s right, when there were cruise missile attacks to try to deal with this weapons of mass destruction, and the fact that he was not cooperating with the weapons inspectors. And of course, you can go back to ’91 when we found that his weapons programs had been severely underestimated by the IAEA and others. So I think that is what people are reminding us, what the intelligence said prior to the war.

Did you know we were at war in 1998? It slipped right by me. But lo, here’s an article on the Weekly Standard web site about the glorious “Four Day War” of 1998.

Of course, the Weekly Standard probably didn’t call it a Four Day War in 1998. I’m not a Weekly Standard subscriber and don’t have access to their archives, so I don’t know for sure. But considering that this glorious little war began on December 16, 1998, and that the House began formal hearings to impeach President Clinton on December 19, 1998, it doesn’t seem some people were standing behind their President in time of war. Or maybe they were behind him, but they had knives out at the time.

In fact, Condi and the Weekly Standard were both taking part in a “Clinton did it too” propaganda effort designed to blame President Clinton for President Bush’s “mistake” about the WMDs. The Four Day War, not recognized as such as the time, was declared retroactively for political expedience. My point is that wars are getting awfully subjective these days. Right now most of us on the Left think of the War on Terror as a metaphor, but righties see it as a real shootin’ war, by damn, just like WWII. If John Wayne were alive he’d be makin’ movies about it already.

When is a war, a war? We know there’s a war when Congress declares war, but what about undeclared wars?

I wrote about this last December, and our own alyosha added an excellent analysis in the comments that deserves another read. In a nutshell, it appears we’re moving into a new phase of history in which wars between nations will be rare. Instead, “wars” will be waged by decentralized organizations with no fixed national boundaries or territories. Such wars won’t have recognizable ends, because there won’t be a surrender or a peace treaty. It’s likely we’re going to be involved in some level of military actions against such organizations pretty much perpetually for the rest of our lives. What seemed to be a state of emergency after 9/11 is now the new normal.

I believe we need to re-think constitutional war powers in light of this new reality.

The Constitution [Article I, Section 8] says Congress shall have power

To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water;

To raise and support Armies, but no Appropriation of Money to that Use shall be for a longer Term than two Years;

To provide and maintain a Navy;

To make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces;

To provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions;

To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United States, reserving to the States respectively, the Appointment of the Officers, and the Authority of training the Militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress …

On the other hand, the President (Article II, Section 2)

The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States.

Now, I interpret that to mean that the President’s military role is subordinate to Congress’s military role. In any event, Congress is supposed to be the part of government that decides whether we’re at war or not. But then there’s the pesky War Powers Act, which says,

The constitutional powers of the President as Commander-in-Chief to introduce United States Armed Forces into hostilities, or into situations where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances, are exercised only pursuant to (1) a declaration of war, (2) specific statutory authorization, or (3) a national emergency created by attack upon the United States, its territories or possessions, or its armed forces.

Dahlia Lithwick provides background on the War Powers Act here. See also John Dean. Both of these articles were written immediately after 9/11, before we were publicly talking about invading Iraq.

For the moment I’m putting aside consideration of how closely Bush is adhering to the War Powers Act provisions. Instead, I just want to suggest that Congress revisit the statutory authorization thing so that future presidents can’t fear-monger the nation into a war that drags on for years after the original causes of the war were found to be smoke and mirrors.

It’s one thing to give a President some room to maneuver in case of emergency, and he has to act to protect the United States and its territories before Congress can get itself together to declare anything. But when there is no emergency, especially no emergency to the territory of the United States, I see no reason for Congress to hand off its war-declaring powers to the President. No more undeclared wars. If someone can think of a reason this would be a bad idea, I’d like to hear it.

If the President wants to use some limited military action — say, a four-day bombing campaign — Congress can give permission — a “use of force” resolution — but Congress should stipulate limits (in time or resources, or both), and it must be made clear that this resolution is not equivalent to a war declaration and the President is not to assume any special “war powers.” That is, he’s not to assume any powers the Constitution doesn’t give him in peacetime.

What if a President declares an emergency and starts a war per clause 3 in the paragraph above, but Congress looks on and says, WTF? There’s no emergency! There should be some way for Congress to be able to rein in the President in this circumstance — Sorry, no emergency! You’ve got so many days to bring the troops back, or it’s mandatory impeachment! I’m not sure how that would be done, but it’s clear we need to provide for it to keep future Bushes in check.

Regarding presidential war powers — the Constitution makes no provision for presidents to take on extra powers during war. In the past, some presidents have taken extraconstitutional actions when they believed it was necessary to save the nation from an enemy or insurrection. Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus is the standard example. People still argue whether he was justified in doing so, but the circumstances were extreme — citizens, not just armies, were shooting and killing each other and were also shooting at militia called to Washington to protect the capital. In some places civil authority had completely broken down. And Lincoln acted openly, not secretly, and he made it clear he was only taking this action without prior consent of Congress because Congress was not in session and the emergency was dire. When Congress came back into session Lincoln requested approval for his actions. The power he had used rightfully belonged to Congress, and he didn’t claim otherwise.

Bush, on the other hand, acts in secret, and usurps powers of Congress when Congress is in session. There’s no excuse for that unless the threat to the nation is immediate — a mighty enemy navy is about to land in Oregon, for example. Otherwise, he is obliged to work with Congress and abide by laws written by Congress, as I argued in the last post. Otherwise, he’s setting himself up to be a military dictator.

So on the first day of the Post-Bush era, when we have a new birth of freedom and can begin to function as a real democracy again, we should come up with some laws — maybe even a constitutional amendment to be sure it sticks — that will be binding on future presidents and congresses. Vietnam might have been a fluke, but Vietnam and Iraq in one lifetime reveal a flaw in the system that needs correcting.