I completely forgot that yesterday was “National Sanctity of Human Life Day.†At The Reaction, Capt. Fogg describes how the day was commemorated.

Category Archives: Iraq War

Drafty

Andrew J. Bacevich has an intriguing op ed in today’s Boston Globe that presents another side to the question, “to draft, or not to draft.” His argument is that an all-volunteer army has created a U.S. Army that is completely estranged from U.S. society. I’m not necessarily endorsing a draft, but I am presenting Bacevich’s view for your consideration.

Historically, Americans had viewed a “standing army” with suspicion. After Vietnam they embraced the idea. By 1991 they were celebrating it. After Operation Desert Storm — with its illusion of a cheap, easy victory — soldiers like General Colin Powell persuaded themselves that “the people fell in love with us again.”

If love, it was a peculiar version, neither possessive nor signifying a desire to be one with the beloved. For the vast majority of Americans, Desert Storm affirmed the wisdom of contracting out national security. Cheering the troops on did not imply any interest in joining their ranks. Especially among the affluent and well-educated, the notion took hold that national defense was something “they” did, just as “they” bus ed tables, collected trash, and mowed lawns. The stalemated war in Iraq has revealed two problems with this arrangement.

The first is that “we” have forfeited any say in where “they” get sent to fight. When it came to invading Iraq, President Bush paid little attention to what voters of the First District of Massachusetts or the 50th District of California thought. The people had long since forfeited any ownership of the army. Even today, although a clear majority of Americans want the Iraq war shut down, their opposition counts for next to nothing: the will of the commander-in-chief prevails.

The second problem stems from the first. If “they” — the soldiers we contract to defend us — get in trouble, “we” feel little or no obligation to bail them out. All Americans support the troops, yet support does not imply sacrifice. Yellow-ribbon decals displayed on the back of gas-guzzlers will suffice, thank you.

Bacevich is a West Point graduate and Vietnam veteran with 23 years of service in the U.S. Army. Today he is a professor of international relations at Boston University.

It so happens I have an advance review copy of Chalmers Johnson’s upcoming book, Nemesis. I’ve read enough of it to know that lots of you folks will probably want to read it. Anyway, Chalmers Johnson quotes Bacevich,

Americans in our own time have fallen prey to militarism, manifesting itself in a romanticized view of soldiers, a tendency to see military power as the truest measure of national greatness, and outsized expectations regarding the efficacy of force. To a degree without precedent in U.S. history, Americans have come to define the nation’s strength and well-being in terms of military preparedness, military action, and the fostering of (or nostalgia for) military ideals. [Andrew Bacevich, The New American Militarism: How Americans Are Seduced by War (Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 2]

Now, lots of us have noticed that while righties romanticize the military, and they fancy themselves great supporters of the military, they aren’t real big on joining the military. This seems to me to support Bachevich’s thesis. To see an example of the weird way the Right objectifies the troops, see this recent post by Dean Barnett. Barnett has a snit because Pelosi referred to the late Marine Corporal Jason Dunham, who died in Iraq at the age of 22, as a “young man.” Barnett writes,

I know the Democrats have developed as one of their pet Lakoffian tics the habit of describing our warriors as defenseless children. Thus, when Pelosi refers to Dunham as a “young man†and the men he saved as “other young people,†she’s merely falling into a bad habit.

But it’s a real bad habit; a truly offensive one. This is a matter of more than just mere semantics. Jason Dunham was a Marine. So, too, were the men he saved. They see themselves as warriors, and that’s what they are. The term “young people†is meant to demean them, and in Dunham’s case denies him the dignity that he has so completely earned.

A 22-year-old man is a young man. This is not demeaning. I don’t see anything demeaning about referring to people as, well, people, young or otherwise. And soldiers are people. But not to Barnett, it seems.

Additionally, the failure to use the word “soldierâ€, “Marine” or any other term that acknowledges a connection between Dunham and the military is borderline grotesque. In Pelosi’s formulation, it almost sounds as if some random “young people†were frolicking in Iraq and stumbled upon a live grenade.

One other thing: If Dianne Sawyer really wants to see human beings that are like “galvanized steel,†she might consider turning her journalistic gaze to Iraq and the Marines still there like Jason Dunham.

It is not an insult to Marines to acknowledge that they are human beings. But to Barnett, Marines are not people. They are not made of tender flesh and blood, but galvanized steel. They aren’t human, but objects.

Let’s go back to Bacevich’s Boston Globe column:

Stipulate for the sake of argument that President Bush is correct in saying that failure in Iraq is not an option. Then why limit the “surge” to a measly 21,500 additional troops? Why not 50,000? With the population of the United States having now surpassed 300 million, why not send 100,000 reinforcements to Iraq?

The question answers itself: There are not an additional 100,000 Americans willing to commit their lives to the cause. Even offering up 21,500 finds the Pentagon scraping the bottom of the barrel, extending the tours of soldiers already in the combat zone while accelerating the deployment of those heading back for a second or third tour of duty.

After the Cold War, Americans came to see war as something other than a human enterprise; the secret of military superiority ostensibly lay in the microchip. The truth is that the sinews of military power lie among the people, who legitimate war and sustain it.

For the United States to remain a great military power will require a genuine reconciliation of the military and American society. But this implies the people exercising a greater say in deciding when and where American soldiers fight. And it also implies reviving the tradition of the citizen-soldier so that all share in the burden of national defense.

Now, I’m sure it’s the case — it’s what everybody says, anyway — that from a purely military perspective a professional force is superior to an army of draftees. But what about what Bacevich writes, about the relationship between society and the military?

Add to this what I wrote in an earlier post, that America will have to choose between being an empire and being a republic; we cannot be both. I am more and more persuaded this is so, and that we have already reached the fork in the road (if not passed it).

Steppenwolf

Since we’ve been talking about the antiwar movement or lack thereof –at the Washington Post, John McMillian writes a column called “Missing in Antiwar Action” wondering why young people aren’t engaging in the antiwar movement. McMillian is a Harvard history professor, and his column is mostly about the low-key reaction to the war by his students. An obvious reason is the lack of a draft, of course. McMillian suggests some other reasons:

First, today’s young people claim to be under more pressure to succeed than we were. I believe this is true, and I’ll elaborate in a minute. But I think it’s a lame excuse.

Second,

… today the gauzy idealism that circulated among teenagers in the 1960s seems almost freakishly anomalous. According to a recent U.S. Census report, 79 percent of college freshmen in 1970 said that “developing a meaningful philosophy of life” was among their goals, whereas only 36 percent said becoming wealthy was a high priority. By contrast, in 2005, 75 percent of incoming students listed “being very well off financially” among their chief aims.

Certainly, acquiring wealth was less of an issue for us because we grew up at a time when the American middle class got more affluent every time it breathed. The road ahead didn’t seem all that intimidating when viewed from the 1960s — a big reason, I suspect, we may have felt less pressured than students today. We would have a harder time than we realized, since the post-World War II economic growth that seemed endless to us peaked about 1972. The economy slowed down after 1973 and never quite recovered. Although it may be that Boomers as a group are less frugal than our parents were, we struggled more than our parents did — with two-income families, for example — to keep up appearances. And I think our children will find appearances slipping no matter how hard they work. It’s bleak out there.

Some of my students suggested that they might not even be capable of experiencing the kind of indignation and disillusionment that spurred many baby boomers toward activism. In the Vietnam era, the shameful dissembling of American politicians provoked outrage. But living in the shadow of Vietnam and Watergate, and weaned on “The Simpsons” and “The Daily Show,” today’s youth greet the Bush administration’s spin and ever-evolving rationale for war with ironic world-weariness and bemused laughter. “The Iraq war turned out to be a hoax from the beginning? Figures!”

As I wrote last week, we Boomers were raised to be naive and idealistic. As we caught on to what our government actually was doing, we felt betrayed. Most of us remained idealistic, however, even as we protested the government. Consider also that our parents had gone from being the Greatest Generation in the 1940s to being the “Gray Flannel Suit” generation in the 1950s — from military regimentation to social and cultural regimentation, creating a society so oppressively conformist that if the hem of one’s skirt deviated by even a half inch from standard specifications — mid-knee length in a below-the-knee year, for example — eyebrows were raised. Of course, hair length on the boys was every bit as regimented, and facial hair (other than the occasional rakish mustache à la David Niven) was a no-no.

Naturally, when the Boomers hit adolescence the cry of rebellion was heard throughout the land. We decorated ourselves with beads and feathers and wore our hair and our skirts any length we damn well pleased. The books we all read were mostly about either oppression, liberation, or transcendence — 1984, Animal Farm, Hesse’s Siddhartha and Steppenwolf (although you might not have made it all the way through Steppenwolf), The Prophet, Jonathan Livingston Seagull (you tried to forget that one, didn’t you?), The Lord of the Rings.

What are the young folks reading these days? I don’t even know.

McMillian’s piece ends rather bleakly:

“Just like [in] the 1960s, we have an unjust war, a lying president, and dead American soldiers sent home everyday,” one student wrote me in an e-mail. “But rather than fight the administration or demand a forum to express our unhappiness, we accept the status quo and focus on our own problems.”

That’s sad, considering the status quo is even bleaker for them than it was for us. All the taxes we’re not paying now are going to end up in their laps, for example.

On the other hand, this study from UCLA says —

This year’s entering college freshmen are discussing politics more frequently than at any point in the past 40 years and are becoming less moderate in their political views, according to the results of UCLA’s annual survey of the nation’s entering undergraduates. … the percentage of students identifying as “liberal” (28.4 percent) is at its highest level since 1975 (30.7 percent), and those identifying as “conservative” (23.9 percent) is at its highest level in the history of the Freshman Survey, now in its 40th year.

Good luck, young folks. You’ll need it.

After the Surge

Yesterday Baghdad suffered its worst day of carnage in more than a month. Most of the violence appears to have been at the hands of Shiites, targeting Sunnis.

MSNBC reports that the Sunni nation of Saudi Arabia is thinking about sending troops into Iraq “should the violence there degenerate into chaos.” Would the Saudi troops favor the well-being of Sunnis, while Iran is backing the Shiites? Is this really a good idea?

No one outside the Bush Administration seems to think the so-called “surge” — which Senator Clinton said today is a “losing strategy” — will have any significant impact on the violence. Still, Congress is not moving all that fast to stop it. Renee Schoof writes for McClatchy Newspapers:

Although most Democrats and some Republicans oppose Bush’s 21,500-member troop increase, Congress isn’t moving very fast to try to stop or alter the plan. Democratic leaders in both houses want their first step to be a resolution calling on lawmakers to go on record as being for or against Bush’s Iraq plan.

Democrats say they have a solid Senate majority against the plan, including perhaps one dozen Republicans, so the resolution is effectively a symbolic vote of no confidence in Bush’s war plan. Only after that vote will they look at ways to use Congress’ power over funding as a hammer.

This may make sense as political strategy, but I fear that by the time Congress does anything concrete the “surge” will be a fait accompli.

On the other hand, this was just posted at WaPo —

Sen. Christopher J. Dodd (D-Conn.) announced legislation today capping the number of troops in Iraq at roughly 130,000, saying that lawmakers should take an up-or-down vote on President Bush’s plan to send additional troops to the country and not settle for the non-binding resolution several Senate leaders prefer.

But for the moment, let’s look ahead to post-surge Iraq. Paul Krugman’s column on Monday called the surge/escalation/augmentation the “Texas Strategy.”

Mr. Bush isn’t Roger Staubach, trying to pull out a win for the Dallas Cowboys. He’s Charles Keating, using other people’s money to keep Lincoln Savings going long after it should have been shut down — and squandering the life savings of thousands of investors, not to mention billions in taxpayer dollars, along the way.

The parallel is actually quite exact. During the savings and loan scandal of the 1980s, people like Mr. Keating kept failed banks going by faking financial success. Mr. Bush has kept a failed war going by faking military success.

The “surge†is just another stalling tactic, designed to buy more time.

I wrote something along the same lines last April, although I wrote about Enron CEO Jeffrey Skilling. I wrote then:

It would have worked out if we’d just stayed the course, the chief executive said. Everything would have been fine if people had had more faith. We failed because we were attacked by people who wanted us to fail.

Bush in Iraq? No, Jeffrey K. Skilling in court.

The former Enron CEO, on trial for multiple counts of conspiracy and fraud, told the court yesterday that Enron’s slide into bankruptcy was caused by a loss of faith.

The Enron execs genuinely seem to have believed that if only they could have kept their losses hidden and maintained the illusion of success a little longer, the Good Profits Fairy would have come along and bailed them out eventually. (And who’s to say that the Bush Administration wouldn’t have given them enough war and disaster profiteering contracts that they’d be riding the gravy train today?) So, in their own minds, they did not fail. As for the bad decisions that put them in a hole to begin with — hey, stuff happens.

Bush’s plan seems to me even more cynical. He just wants to keep the illusion going on long enough that the failure doesn’t happen on his watch. The fact that the “illusion” has already mostly evaporated doesn’t seem to bother him.

On the other hand, maybe he still thinks the Victory Fairy will turn up after all. Robert G. Kaiser wrote in the Sunday New York Times:

In other words, the national security adviser told the president 42 months after this disastrous war began that we can still fix it. A few well-placed bribes plus Yankee ingenuity — pulling this lever, pushing that button — can make things turn out the way we want them to.

Kaiser’s article is really good; you should read it all.

Along the same lines, as John Cole of Balloon Juice points out today, the “Who lost Iraq” mythos is already being written. Be sure to read the whole post for examples from rightie blogs. John Cole concludes,

So they have all the bases covered, you see! If we win, it is because these brave stalwarts stuck it out on their blogs, and lavished unrelenting praise on the troops and the President. They stayed the course, you see, and because of them the troops could get the job done!

If we lose, it wasn’t because of anything this administration, the Pentagon, or their blind support for a leadership that didn’t deserve it. It is because of the lying ass media and those pussy Democrats.

Heads, I win; tails, you lose.

Outside the Bush Administration and its True Believers, conventional wisdom says winning in any meaningful sense is no longer an option. The real questions revolve around disengagement (how’s that for a euphemism?) from Iraq — when, and how? And then after that, we’ll all be wallowing in the political fallout for some time.

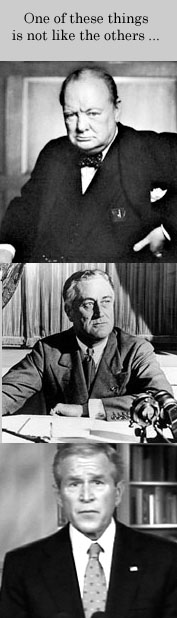

Harold Meyerson has an excellent column in WaPo today discussing how that fallout might fall. He looks at the last two presidents who bailed the nation out of unpopular wars — Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon.

As the first Republican to occupy the White House since the coming of the New Deal, Dwight Eisenhower could have chosen to divide the public and try to roll back Franklin Roosevelt’s handiwork. In fact, he didn’t give that option a moment’s consideration. Social Security and unions, he concluded, were here to stay; any attempt to undo them, he wrote, would consign the Republicans to permanent minority status. Ike also ended the Korean War without attacking Democrats in the process.

And then there’s Nixon —

For Nixon, politics was about dividing the electorate and demonizing enemies. Even as he drew down U.S. forces, he did all he could to inflame the war’s already flammable opponents in the hope that however much the people might dislike the war, they would dislike its critics more.

Do we even have to ask which way the Bushies are likely to go? And consider that the damage Nixon did lived on long after him; much of it is still impacting politics (and hurting Democrats) today. I realize that a lot of people, including me, are impatient with the Dems for being cautious. But they have good reasons to be cautious.

It is possible to lose even if we win. By that I mean that it’s possible the Dems could grow the spine to confront the President and force a withdrawal from Iraq, and yet get the worst of the post-war fallout, which would put the Republicans back in business.

It’s likely that the aftermath of our Iraq adventure will be a nasty business, both here and in the Middle East. Please note what I’m saying here. I’m not saying we should stay in Iraq, but that it’s possible the violence and destabilization will escalate after we leave and create new foreign policy problems that we cannot ignore, the way we pretty much ignored Southeast Asia after Vietnam. I ask again, please read this carefully and don’t whine at me that I am some kind of Bush supporter, because I think these bad things are likely to happen if we stay, also. But the Right is not going to make that distinction, and all crises that arise from the Middle East for the next quarter century are likely to stir up fresh howls about Who lost Iraq? You can bet the Dems in Washington realize this and are thinking hard about it right now.

One Less Dem Hawk

Hillary Clinton says it’s time to start “re-deploying” (per ABC News) troops out of Iraq.

Murtha’s Plan

Just posted at The Nation by Ari Berman:

At a hearing on Iraq today convened by the Congressional Progressive Caucus, Congressman Jack Murtha offered a preview of how he plans to reign in the Bush Administration, from the perch of his chairmanship of the Defense Subcommittee on the House Appropriations Committee.

Murtha announced his intention to use the power of the purse try and close US prisons at Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay, eliminate the signing statements President Bush uses to secretly expand executive power and restrict the building of permanent bases in Iraq.

And starting February 17, Murtha will begin holding “extensive hearings” to block an escalation of the war in Iraq and ultimately redeploy US troops out of the conflict. Murtha predicts that a non-binding resolution criticizing Bush’s expansion of the war would pass the Congress by a two to one vote. But he believes that only money, not words, will get the President’s attention.

Be sure to read the whole thing.

Blame Iraq

While I was writing this, the BBC reported that U.S. troops stormed the Iranian consulate in the northern Iraqi town of Irbil and seized six members of staff.

In reviewing last night’s speech, Walter Shapiro wrote in Salon:

Ever since Bush denounced the theretofore unknown “Axis of Evil” in his 2002 State of the Union Address, at a moment when the nation was still fixated on the horrors of Sept. 11, it has been instructive to listen for new rhetorical gambits in major presidential speeches. That is why it is possible that the most fateful words that Bush uttered from the White House library on Wednesday night were these: “Iran is providing material support for attacks on American troops. We will disrupt the attacks on our forces. We will interrupt the flow of support from Iran and Syria.”

Even though the Democrats have won the rhetorical war in labeling the Bush war plan as escalation, 21,000 additional troops is pretty small potatoes by the standards of prior wars such as Vietnam. But expanding the battlefield to the borders of Iran and Syria — if that was indeed what Bush was suggesting — now that would qualify as escalation, as even Henry Kissinger might admit.

See rege at The Carpetbagger for more discussion. This truly is the part of the speech that needs the most scrutiny and attention.

Oh, and without even looking, I’m willing to bet that one could find critics of the war complaining about the unguarded borders from at least 2005, if not earlier.

Well, on to the reviews —

I have to say one good thing about the New York Times — its editorials beat the pants of the Washington Post’s. Compare/contrast what the two august newspapers cranked out this morning:

I have to say one good thing about the New York Times — its editorials beat the pants of the Washington Post’s. Compare/contrast what the two august newspapers cranked out this morning:

Shorter Washington Post: Risks, obligations, fudge, ponies, maybe, uncertainty, ponies, wait and see. More fudge.

Shorter New York Times: Bleep.

Here’s the first paragraph from the NY Times:

President Bush told Americans last night that failure in Iraq would be a disaster. The disaster is Mr. Bush’s war, and he has already failed. Last night was his chance to stop offering more fog and be honest with the nation, and he did not take it.

It gets better after that.

Over at MSNBC/Newsweek, Howard Fineman is working hard to redeem himself from the days when his fawning deference to Lord Dubya earned him the title Media Whore of the Year.

George W. Bush spoke with all the confidence of a perp in a police lineup….

…if he was trying to assure the country that he had confidence in his own plan to prevent that collapse, well, a picture is worth a thousand words. And the words themselves weren’t that assuring either. Does anyone in America or Iraq , or anywhere else in the world for that matter, really think that the Sunnis and Shia will make peace? Does anyone think that embedded American soldiers won’t be in danger of being fragged by their own Iraqi brethren? Does anyone really think that Iran and Syria can be prevented from playing havoc in Iraq and the rest of the region by expressions of presidential will?

To answer Howie’s question — yes, there are people who think that. There’s no end to the remarkable self-deluding properties of human cognition. But enough of the freak show.

Shorter Boston Globe: Bush won’t face reality.

Shorter Martin Kettle (UK): Blair is screwed.

Now for some substance, from Walter Shapiro, Salon:

Throughout the long century to come, any future leader contemplating sending American troops into combat should carefully watch a tape of George W. Bush’s speech to the nation Wednesday night — and ponder its underlying lessons. This was Bush deflated, his arrogance temporarily placed in a blind trust, looking grayer than ever with his brow furrowed with lines of worry. How humiliating for Bush to be forced to say with a stony face, “The situation in Iraq is unacceptable to the American people — and it is unacceptable to me.”

My take on the “unacceptable” line, in the context of the speech, was that Bush was wagging a finger at Iraqis for being messy. This is from the transcript:

The violence in Iraq — particularly in Baghdad — overwhelmed the political gains the Iraqis had made. Al-Qaida terrorists and Sunni insurgents recognized the mortal danger that Iraq’s elections posed for their cause. And they responded with outrageous acts of murder aimed at innocent Iraqis. They blew up one of the holiest shrines in Shia Islam — the Golden Mosque of Samarra — in a calculated effort to provoke Iraq’s Shia population to retaliate. Their strategy worked. Radical Shia elements, some supported by Iran, formed death squads. And the result was a vicious cycle of sectarian violence that continues today.

The situation in Iraq is unacceptable to the American people — and it is unacceptable to me. Our troops in Iraq have fought bravely. They have done everything we have asked them to do. Where mistakes have been made, the responsibility rests with me.

Is he not saying everything would have worked out if the Iraqis had behaved themselves?

Fred Kaplan at Slate wonders what Bush will do if the Iraqis fail again:

President Bush declared tonight that America’s commitment is “not open-ended” and that “America will hold the Iraqi government to … benchmarks.” However, he said nothing about what will happen if the Iraqis fail to meet those benchmarks. And without a warning (even a sternly intoned “or else!”), benchmarks mean nothing.

And let’s look at those benchmarks. Bush said that the Iraqi government has promised “to take responsibility for security in all of Iraq’s provinces by November.” It “will pass legislation to share oil revenues among all Iraqis.” It will “spend $10 billion of its own money on reconstruction and infrastructure.” It will “hold provincial elections later this year,” to empower local leaders, especially Sunni leaders. And, in a further effort to co-opt Sunni insurgency, it “will reform de-Baathification laws and establish a fair process for considering amendments to Iraq’s constitution.”

When did all these promises get made? Where did Maliki suddenly get the political power, or even the political audacity, to make them? One obstacle to reconstruction has been pervasive corruption within the Iraqi ministries; how does he hope to clean that up? The call for provincial elections has been ignored for months. The Shiite-led government promised to amend the constitution—with special attention to altering the language on oil revenue sharing and de-Baathification—back when the constitution was ratified; it has refused to bring up the issues ever since.

Still, if (if?) the plan fails, Bush will say it is Malaki’s failure, not his. From the transcript:

Only the Iraqis can end the sectarian violence and secure their people. And their government has put forward an aggressive plan to do it.

Our past efforts to secure Baghdad failed for two principal reasons: There were not enough Iraqi and American troops to secure neighborhoods that had been cleared of terrorists and insurgents, and there were too many restrictions on the troops we did have. Our military commanders reviewed the new Iraqi plan to ensure that it addressed these mistakes. They report that it does. They also report that this plan can work.

That’s his exit strategy — blame the Iraqis.

Richard Wolffe, Newsweek:

… if you listened closely to President Bush on Wednesday night, the much-anticipated speech didn’t change the central mission much. It’s clear, hold and build—only this time with money behind it, but not that much money, and not enough new troops to really make a difference. And, Bush signaled loud and clear, it’s really the Iraqis’ problem now.

Yes, the president accepted a degree of responsibility for the failures that have characterized the war in Iraq. “Where mistakes have been made,†he said, “the responsibility rests with me.†But he didn’t go into much detail about what those mistakes were. The basic strategy had been right all along, Bush seemed to be saying. The tactics just needed a little tweaking. …

… Bush reduced the U.S. role to that of loyal watchdog to the Iraqi government. “America will hold the Iraqi government to the benchmarks it has announced,†he said. “If there is change in Iraq, it will have to come almost entirely from the government in Baghdad.”…

…Yet there was little discussion in the speech, or behind the scenes with the Iraqis, of what might happen if they failed to deliver once again. Bush’s aides say that talking about consequences—or threatening withdrawal—will weaken the Iraqi government and embolden insurgents and militias. President Bush simply said that he warned the Iraqi prime minister that the U.S. mission was not “open ended.â€

“If the Iraqi government does not follow through on its promises, it will lose the support of the American people,†he said, “and it will lose the support of the Iraqi people.†It was a curiously impersonal construction. He never suggested the Iraqi leader might lose the support of George W. Bush. And he never mentioned that the polls show a clear majority of Americans opposing his policy of sending more troops to Iraq.

Jack Murtha and others have been saying for months that it’s time for Iraqis to take responsibility for their own country. Now, I personally never saw this as much more than a talking point, to make the bugout seem less ignoble than it might otherwise. As much as I am all for getting out asap, let’s not kid ourselves that we’ll be able to go back to sleep and ignore Iraq after that. Whatever nastiness that goes on once we leave — and there will be nastiness, although not necessarily more nastiness than what will occur if we stay — will be seized by the Right as their next great “stabbed in the back” myth. For the rest of our lives, we’ll have to listen to the whackjobs whine about who lost Iraq? Anticipating this, it appears the politicians of both parties are pinning as much as possible on Iraqis. I can’t say I blame them.

But Bush is still reluctant to let go of his glorious little war, so 20,000 more troops will be tossed into the meatgrinder. Their purpose will be to buy Bush time to knit a bigger butt cover.

But this business about the Iranian consulate worries me; it seems, well, provocative. Is Bush deliberately trying to stir up enough trouble in the Middle East that Congress cannot deny him his 20,000 troops?

See also: Juan Cole, “Bush Sends GIs to his Private Fantasyland“; Glenn Greenwald, “The President’s intentions towards Iran need much more attention.”

Mistakes Have Been Made

OK, I’ll live blog the damnfool speech. You’d better appreciate this.

He’s calling the maneuver a “new strategy.” The violence of Iraq overwhelmed the political games. He’s talking about a vicious cycle of sectarian violence that continues today. This is unacceptable.

“Where mistakes have been made, the responsibility rests with me.” That’s supposed to be the money quote. “Where mistakes have been made” seems a bit weaselly to me.

Holy shit, he mentioned September 11. Stopit stopit stopit!!!

He’s saying that the Iraqis have a new plan — it’s not even our bleeping plan — and he’s claiming that experts (e.g., Barney and the White House goldfish) have reviewed the plan and say it will work. So it’s really the Iraqi plan, not our plan, and we’re just sending five brigades to be embedded in Iraqi units to help Iraiqis clear and support neighborhoods.

This time we’ll have the force levels we need to hold areas cleared of insurgents. No more whack-a-mole. Malaki has pledged sectarian violence will not be tolerated. Well, I feel better.

If the Iraq government doesn’t follow through on its promises, it will lose the support of the American people. He really said that. I think Laura needs to sit him down for a long talk.

He’s wooden. No passion in this speech. He sounds as if he’s announcing the opening of a new supermarket.

He mentioned the Iraq Study Group, as if he’s really paying attention to it.

No one in America is still listening to this. Blah Blah Blah. There’s an episode from Season One of Rome on HBO I’m missing for this.

Our commanders believe we have an opportunity in Anbar Province to strike insurgents, or terrorists, or somebody.

OK, he’s mentioned Iran and Syria. Hmm.

Monotone droning. This is not a good performance. He’s not saying shit he hasn’t already said, so content is not particularly newsworthy.

“There will be no surrender ceremony on the deck of a battleship.” So if we arrange one, will he go away?

On HBO, right now Julius Caesar is chasing Pompey Magnus around Greece. They had real wars in those days, buckaroos.

Oh, gawd, this is a bad speech. Booooring. Same old, same old.

It’s over. Deep breath.

He’s the postgame wrapup. Keith Olbermann says Bush mentioned Lieberman, which must have been while I was flipping to HBO. He also used the word “sacrifice” at some point, as British newspapers had predicted.

Here’s Dick Durbin, Senator from Illinois. Bush is ignoring the advice of his own generals. 20,000 too few to end the civil war, and to many to risk. We have paid a heavy price. We’ve given Iraq a lot, he says. Now in the fourth year of this war, it is time for Iraqis to stand and defend their own nation. They must know that every time they dial 911, we’re not going to send more soldiers. It’s time to begin the orderly redeployment of our troops.

Questions: Durbin used the word civil war with the president, he said.

Chris Matthews’s interpretation is that Bush is calling for a broadening of the war vis à vis Iran and Syria. I want to get a transcript and re-read that part.

Joe Scarborough says most of the Republicans will come back to support the President after the speech after his “clear and sober assessment” of the way forward. Those people are bought cheap.

Barack Obama speaks: The American people and troops have done everything asked of them. An additional 20,000 troops will not help. Obama says he will “actively oppose the president’s proposal.” We should engage in a dialogue with Iran and Syria. The President is saying the same stuff he’s been saying.

Prelude to the Speech

I guess I’ll watch the speech so you don’t have to.

I’m hearing noises from the cable news bobbleheads that Republican support for the escalation is weak and crumbling. I can’t tell from current news stories how widespread the Republican insurgency might be. If a substantial number of congressional Republicans fall away, and vote no even on a non-binding resolution, this could pave the way for bigger and better things in the future — like a binding vote to de-fund the war. And how’s about impeachment?

Jonathan Turley on Countdown — The president can only spend funds that are given to him by Congress, he says. Go back to the Mexican War to see conditions put on funds. Congress prevented the U.S. to go into Angola and to get out of Somalia. The framers of the Constitution deliberately divided the war powers between Congress and the President. They wanted these two branches to negotiate and cooperate on decisions to go to war.

Non-binding resolutions are the same thing as doing nothing at all Turley says. But Congress can stipulate that no money in an Iraq appropriation bill might be used in a surge. If Dubya tries a signing statement countermanding the clear will of Congress on an appropriations bill, it would be nothing short of theft.

At the Washington Post, Dan Froomkin says the escalation is a change of tactic, not strategy.

Peter W Galbraith explains why the surge won’t work.