According to the McKinsey Global Institute, the United States now spends more on health care than it does on food. Is that self-evidently screwy, or what?

I looked up McKinsey Global Institute because Paul Krugman mentioned it in his Friday column, “Health Care Excuses.”

Excuse No. 2: It’s the cheeseburgers.

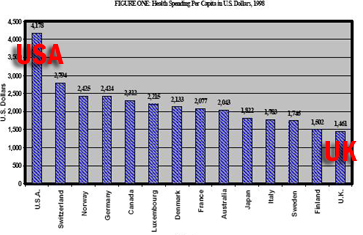

Americans don’t have a bad health system, say the apologists, they just have bad habits. Overeating and teenage sex, not the huge overhead of America’s private health insurance companies — the United States spends almost six times as much on health care administration as other advanced countries — are the source of our problems.

There’s a grain of truth to this claim: Bad habits may partially explain America’s low life expectancy. But the big question isn’t why we have lower life expectancy than Britain, Canada or France, it’s why we spend far more on health care without getting better results. And lifestyle isn’t the explanation: the most definitive estimates, such as those of the McKinsey Global Institute, say that diseases that are associated with obesity and other lifestyle-related problems play, at most, a minor role in high U.S. health care costs.

In truth, American fast food circles the globe. And native cuisines of other nations are not necessarily health food. Have you ever been subjected to a full English breakfast? There’s probably less cholesterol in cheeseburgers.

The other excuses, btw, are (1) people without insurance get health care, anyway; (3) we get better medical care now than we did 50 years ago, so the money is well spent; and (4) socialized medicine! Krugman explains why these excuses are bogus.

On the same day this column was published, the Heritage Foundation released its own assessment of America’s health care:

The debate over government-run health care has roiled for decades. Today, we’re at the tipping point.

Incremental growth in public health programs has brought us to the brink. Today, almost half of America’s children — 45 percent — have their health care paid for by taxpayers. The children’s health bill (SCHIP) now before Congress would boost this to 55 percent. And that’s the tipping point.

Once most children are covered by taxpayers, the remaining children will shortly follow. Then their parents. Then those with no children at home. Eventually, the whole country would be under Washington-run health care, using tax dollars to pay the bills.

Even without a megabillion-dollar SCHIP expansion, taxpayers already pick up the tab for almost half the health care in America, via Medicare, Medicaid and the Veterans Administration. The SCHIP expansion could tip that, too, so the majority of all health care — not just kids’ care — is government-paid and therefore government-controlled.

If Congress overrides President Bush’s SCHIP expansion veto, the full and final federal government takeover of medicine in America becomes inevitable. With that would come lower quality health care, long waits and explicit government rationing of care. That’s the story wherever countries have nationalized their health systems.

That last part is a lie. It’s true the national health care systems of some countries, notably Britain and Canada, have hit some bumps. But most countries with national health care do not have “lower quality health care, long waits and explicit government rationing of care.” The fact is that, in measure after measure, the U.S. health care system is actually below average. It’s true that we still manage to lead the world in some aspects of health care, such as cancer survival rates. But I explained here why our glorious cancer survival rates are not really all that glorious.

And I bet no Brit or Canadian has to line up to get health care in old animal pens.

Heritage continues,

SCHIP expansion also distracts from efforts to make health care more affordable. That would require a reversal of the Washington-dictated bureaucracy that is pandemic in American medicine and drives up costs — as illustrated by 135,000 pages of federal regulations that hog-tie doctors and hospitals. Reduce the bloated bureaucracy, and you reduce the costs.

[Update: Turns out the 135,000 pages is a myth, and an old myth, at that. From the comments of Rep. Pete Stark, House Ways and Means Committee, hearing on Medicare Reform, March 15, 2001.

Mr. STARK. Don’t mention that to the good folks in the 13th District of California, please.

There is no business operation–and that is what HCFA is–that can’t stand improvement and doesn’t need constant revision to see that we are using current technology. In fact, we are offering you a buck off, I think, if you will file electronically. Maybe we should charge you a buck–you being your group and other participating doctors–if you don’t file electronically to urge you to get out and buy that laptop and help us be more efficient.

There are a lot of ways we can cooperate, but the MERFA may very well completely eliminate any ability to enforce our laws and regulations. It is not the way to go. And I would urge you to–which is unlike previously, 10 years ago with the AMA–continue to be in the tent with us as we write any improved legislation, and I think we can go a long way together.

But, please, you know, for a lot of the guys who work hard, this argument 135,000 pages of regulations is baloney. We have counted them. There are about 35,000, which is maybe too many, but it isn’t 135,000. That number came from Mayo, who have refused to send us any documentation of where it came from. But, believe me, I want to stay out of the Mayo Clinic if they can’t tell the difference between 135,000 and 35,000, or when they read my cholesterol level, I am going to have a real problem.

So thank you for your organization’s support to stop smoking, to get kids insured, to reform managed care. But remember that one of the complaints you have that are fixed in the Patients’ Bill of Rights is that you get paid by the private insurers on time. At least we do that. We may come back after you later, and maybe we have to change that. But be careful what you wish for. It could come to pass. And I look forward to working with you.

I take it the 135,000 pages is a kind of urban legend that’s been around for a while.]

I googled around for some concrete examples of how federal regulations “hog-tie doctors and hospitals” and run up costs. There are probably other examples, but all I found was this: The EPA has issued some regulations regarding disposal of “infectious waste,” defined as “microbiologic (stocks, cultures); blood products; pathology waste (tissue and organs); sharps, including needles and blades; animal carcasses, body parts, and bedding from infected animals; and bedding and waste from patients placed in health-related isolation.” Some of these regulations came about after health care residue such as bloody gauze and used hypodermics washed up on some beaches. But if you don’t mind the beaches, I suppose it would save a little money to let hospitals dump this stuff any way they want.

But I don’t see how relaxing pathology waste regulations is going to change the fact that the United States spends almost six times as much on health care administration as other advanced countries. I bet most of those other countries have regulations, too, since they’re all have socialized medicine.

I still say that if “market forces” could have found a way to solve the health care crisis, it would have done it by now.

But here’s something else alarming, picked up from Paul Krugman’s blog.

Two important articles co-authored by Peter Orszag, the director of the Congressional Budget Office.

The first emphasizes a point I’ve also tried to get at:

The long-term fiscal condition of the United States has been largely misdiagnosed. Despite all the attention paid to demographic challenges, such as the coming retirement of the baby-boom generation, our country’s financial health will in fact be determined primarily by the growth rate of per capita health care costs.

In other words, Social Security is not the big problem (and it’s not in “crisis,†Sen. Obama); it’s Medicare and Medicaid, and their problems are wrapped up in a general health-care crisis.

In other words, if we don’t retire the bleeping “free market” health care system, we’re doomed.

The second has a lot to say about controlling costs, and also explains succinctly, albeit in slightly obscure terms, why “consumer-directed†care, which is at the core of all the Republican plans, won’t work:

On the consumer side, higher deductibles would encourage patients to be more prudent in their use of services, but they also raise concerns about the financial burden on persons with major health problems. Furthermore, the concentration of health care spending among a relatively small percentage of the population with very high costs limits the effect on total spending of increased cost sharing for initial charges.

In short, making people pay more for things like doctors’ visits is going where the money isn’t. The big bucks go for big expenses like cardiac surgery — and either these things are paid for by insurance, or not at all.

Cutting-edge medical science of a mere century ago was nearly medieval compared to what we have now. My father used to claim that, in his youth, tonsillectomies were performed on a kitchen table, and the chief surgical instrument was a hot spoon. My dad used to embellish a tad, but the fact remains that most of the really expensive procedures and equipment didn’t exist until the 1940s or later. Before then, there was no open-heart surgery, no MRIs, no chemotherapy, no dialysis. Mass production of the first antibiotic, penicillin, didn’t begin until 1943.

Before the 1940s, “consumer-directed” medical care probably was as economically efficient as any other consumer service. But for the past few decades medical care has become so expensive that only the extremely wealthy can pay for it. So consumers were cut out of the system a long time ago. Now we have an insurance company-directed health care system, and the health care sector is eating all our other economic sectors.

Heritage claims “taxpayers already pick up the tab for almost half the health care in America.” Heritage is not famous for its factual accuracy, but let’s assume for a moment that’s true. What we’ve basically done over the years is patch together some government programs to take over some parts of the population the private insurance companies weren’t serving — to pick up the droppings from the private health insurance table, so to speak. Put another way, we’ve created a mess of government programs to help maintain the fiction that our “free market” health insurance system works just fine. As they say in Britain, brilliant.

Today

Today