Democrats are becoming the party of choice for the wealthy, according to several recent op eds. Let’s review.

It’s already been noted that business sectors, with the exception of petrochemicals, are donating more to Dems and less to Republicans for the first time in a great many years. People with profits in mind think the Republicans are far too stuck on God, guns, and gays.

But wealth is also about protecting and exploiting its advantages, and Dems are ready to help. Yesterday Paul Krugman asked if Dems were “wobbled by wealth.”

The most conspicuous example of this influence right now is the way Senate Democrats are dithering over whether to close the hedge fund tax loophole — which allows executives at private equity firms and hedge funds to pay a tax rate of only 15 percent on most of their income.

Only a handful of very wealthy people benefit from this loophole, while closing the loophole would yield billions of dollars each year in revenue. Retrieving this revenue is a key ingredient in legislation approved by the House Ways and Means Committee to reform the alternative minimum tax, something that must be done to avoid a de facto tax increase for millions of middle-class Americans.

A handful of superwealthy hedge fund managers versus millions of middle-class Americans — it sounds like a no-brainer.

But as The Financial Times reports, “Key votes have been delayed and time bought after the investment industry hired some of Washington’s most prominent lobbyists to influence lawmakers and spread largesse through campaign donations.†It goes on to describe how Harry Reid, the Senate majority leader, was “toasted by industry lobbyists†(and serenaded by Barry Manilow) at a money-raising party for his special fund to help Democrats get elected next year.

Is this the shape of things to come?

No, it’s not the shape of things to come. It’s the shape of what’s been going on for a long time, in both parties.

But Michael Franc wrote in yesterday’s Financial Times that “Democrats wake up to being the party of the rich.”

The decision by Senate majority leader Harry Reid, the Nevada Democrat, surprised many Washington insiders, who saw the plan as appealing to the spirit of class warfare that infuses the Democratic party. Liberal disappointment in Mr Reid was palpable at media outlets such as USA Today, where an editorial chastised: “The Democrats, who control Congress and claim to represent the middle and lower classes, ought to be embarrassed.”

Far from embarrassing, this episode may reflect a dawning Democratic awareness of whom they really represent. For the demographic reality is that, in America, the Democratic party is the new “party of the rich”. More and more Democrats represent areas with a high concentration of wealthy households. Using Internal Revenue Service data, the Heritage Foundation identified two categories of taxpayers – single filers with incomes of more than $100,000 and married filers with incomes of more than $200,000 – and combined them to discern where the wealthiest Americans live and who represents them.

Democrats now control the majority of the nation’s wealthiest congressional jurisdictions. More than half of the wealthiest households are concentrated in the 18 states where Democrats control both Senate seats.

The Financial Times implies that the concentration of wealth in Blue states also is a new thing, but it isn’t. Massachusetts and California didn’t become more liberal and more prosperous than Alabama and Mississippi last week. The more affluent states have tended to be more liberal for a long time. I’ll put the chicken ahead of the egg and say that these states are not more likely to elect Democrats because they are more affluent, but rather are more likely to be affluent because they elect Democrats. States that are more willing to tax themselves and provide better public education, well-maintained infrastructure, wider “safety net” programs and other social services will, in the long run, be more prosperous generally than states that let let education, infrastructure, etc., rot.

Yes, Democrats, like Republicans, are too influenced by Money, but they’re not as “wobbled” by right-wing ideology as are Republicans.

I’ve argued many times, such as here, that the U.S. became the world’s biggest economic powerhouse in the 20th century because, for a time, we invested in ourselves. And we are in danger of losing that status because of our own stinginess to each other.

A blog called “Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science” shows us another factor:

It is characteristic of the east and west coasts that the richer areas tend to be more liberal, but in other parts of the country, notably the south, the correlation goes the other way. A comparable journey in Texas would go from Collin County, a suburb of Dallas where George W. Bush received 71% of the vote, to rural Zavala County in the southwest, where Bush received only 25%. … there is a clear pattern [in Texas] that poor counties supported the Democrats while the Republicans won in middle-class and rich counties. …

… By comparison, the next graph shows the counties of Brooks’s home state of Maryland: here there is no clear pattern of county income and Republican vote. We have indicated Montgomery County, the prototypical wealthy slice of Blue America, in bold, and it is not difficult to find poorer, more Republican-supporting counties nearby as comparisons. Rich and poor counties look different in Blue America than in Red America.

Consider also this old Paul Krugman column. On the whole Red states receive more federal aid than they pay in federal taxes; wealthier Blue states pay more federal taxes than they get back. “Over all, blue America subsidizes red America to the tune of $90 billion or so each year.” But Red states tend to have more social problems — “Children in red states are more likely to be born to teenagers or unmarried mothers — in 1999, 33.7 percent of babies in red states were born out of wedlock, versus 32.5 percent in blue states. National divorce statistics are spotty, but per capita there were 60 percent more divorces in Montana than in New Jersey. ”

My understanding is that in more affluent states, wealthier people more often vote Democratic and poorer people more often vote Republiican, but in poor states it’s the other way around. I postulate that one reason many poor states are poor is that they’ve been run by a right-wing establishment for a long time. The wealthy of the poorer Red states, members of the establishment, align themselves with Republicans to keep their plutocratic power and privilege. The wealthy of the more affluent Blue states are more likely to appreciate the higher overall standard of living that a reasonably progressive government can enable.

At the same time, the less wealthy of Red states may have a greater appreciation of economic populism than their counterparts in Blue states.

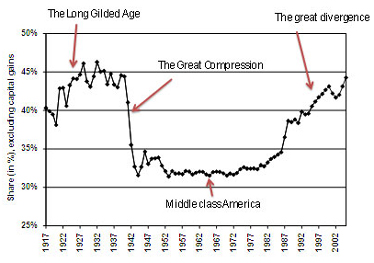

Even so, in election cycles from 1976 to 2004, Democrats did much better among the poor than the rich in the nation overall. Maybe that difference is narrowing. But suddenly declaring that the Dems are the party “of the rich,” as the Financial Times is doing, strikes me as the cheap promotion of a cooked-up talking point.

Elsewhere, Jonathan Rauch asks “Can Democrats Own Prosperity?” Since the 1950s, he says, pollsters have asked the question “Looking ahead for the next few years, which political party do you think will do a better job of keeping the country prosperous?” And Rauch provides a chart that shows Dems generally owned that question until Ronald Reagan came along.

The chart begins in 1951, when Harry Truman was president, and it shows how decisively the Depression and New Deal had bestowed “party of prosperity” status on the Democrats. Only occasionally did the Republicans even touch them. The Democrats’ prosperity advantage seemed to be their birthright, part of the natural order of things, unlikely to be challenged or changed. Even well into the 1970s, as stagflation set in, few Democrats foresaw the trouble ahead.

That trouble arrived in the person of Ronald Reagan, whose greatest political achievement was to seize prosperity for the Republicans. He knew what he was doing when he made famous the phrase, “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” By the time he was finished, Reagan had exorcised Herbert Hoover’s ghost. Now it was the Democratic Party, once seemingly synonymous with modern economic management, that seemed inept and obsolete.

A recession and a bumbling Republican campaign nonetheless helped put a Democrat in the White House in 1993, and the succeeding eight years brought the Democrats news both good and bad. The good news was that a turbocharged economy lifted them back to parity. The bad news was that a turbocharged economy lifted them only to parity. Perhaps the memory of stagflation was too fresh in the public’s mind; perhaps divided government muddied the picture. For whatever reason, by the time George W. Bush took office, the Democrats had not made the sale. The country had no party of prosperity.

Seeing opportunity, Bush set out to recapture and fortify Reagan’s redoubt. His weapon was tax cuts—large and aggressive ones. That, plus five years of economic growth, should have pleased the public.

The results? Devastating. Crushing. Not only did Bush and his party fail to make the sale, the public slammed the door in their faces. Just why is hard to say. Worries about economic insecurity, and the failure of the median household income (adjusted for inflation) to rise during the Bush years, undoubtedly played a part. Bush’s personal unpopularity and the public’s displaced anger over the Iraq war may also figure.

In any case, by September 2006, Democrats had opened up a 17-point lead on prosperity. This September, the gap widened to 20 points, confirming that the change was no fluke. Democrats enjoy a lead on prosperity whose like they have not seen in a generation.

Rauch suggests that to maintain this advantate, Dems need a prosperity “narrative.” The right-wing “supply side” narrative is no longer selling, but Dems have yet to come up with a counter-narrative.

Various bits and pieces are in circulation. Fix health care. Improve income security. Restrict trade. Raise taxes on the rich. Democrats hope to speak to middle-class America’s feelings of economic vulnerability, which is probably the right tree to bark up. But while some Democrats strike notes of class resentment, others seem to blame foreigners. No candidate has found a package and a tone that tell a story not primarily about populism or nationalism but about prosperity: raising the tide to lift all boats.

I’ve got one: Let’s invest in ourselves. The ad running in the left-hand column says “Invest in the Home Front,” but I’d like to get away from war metaphors.

As for the influence of the malefactors of great wealth on politics, this is an old and deeply entrenched problem that probably will never go away completely. Public campaign finance would help minimize the beast, however.

See also BooMan and Kevin Drum.