David Leonhardt writes about Peter Georgescu, a “chairman emeritus” of Young & Rubicam.

Peter Georgescu — a refugee-turned-C.E.O. who recently celebrated his 80th birthday — feels deeply grateful to his adopted country. He also feels afraid for its future. He is afraid, he says, because the American economy no longer functions well for most citizens. “For the past four decades,” Georgescu has written, “capitalism has been slowly committing suicide.”

This is hardly news; a lot of people have noticed that capitalism as currently practiced is not sustainable. I certainly don’t think capitalism in its current form is sustainable. My only question is whether it will take the rest of us and the planet with it when it goes. See, for example, “Capitalism Is Devouring Itself” and “Destroying Capitalism to Save It” from The Mahablog archives. This is in the New York Times because a big-shot capitalist admits it’s true.

Georgescu’s life story is about how a Romanian boy who grew up with Nazi and then Soviet occupation escaped from behind the Iron Curtain and made good in America. He succeeded because he got a lot of help from people who were inspired by his story and opened doors for him.

“The hero of my story,” Georgescu said to me “is America.” Over and over, he said, people who didn’t have any obvious reason to care about him helped him: the congresswoman who didn’t represent his parents’ district; the headmaster who’d never met him; the ad executives who mentored him.

All of them, he believes, were influenced by a post-World War II culture that (while deeply flawed in some ways) fostered a sense of community over individuality. Corporate executives didn’t pay themselves outlandish salaries. Workers enjoyed consistently risingwages.

Things began to change after the 1970s. Stakeholder capitalism — which, Georgescu says, optimized the well-being of customers, employees, shareholders and the nation — gave way to short-term shareholder-only capitalism. Profits have soared at the expense of worker pay. The wealth of the median family today is lower than two decades ago. Life expectancy has actually fallen in the last few years. Not since 2004 has a majority of Americans said they were satisfied with the country’s direction.

Peter Georgescu also is the author of a few books, including Capitalists, Arise! End Economic Inequality, Grow the Middle Class, Heal the Nation. In 2015 he wrote an op ed for the NY Times titled Capitalists Arise: We Need to Deal With Income Inequality. So, up to a point, he gets it. Leonhardt continues,

He talks about the signs of frustration, in both the United States and Europe. He has seen societies fall apart, and he thinks many people are underestimating the risks it could happen again. “We’re not that far off,” he told me.

I agree; I think if current trends are not reversed pretty damn soon we face a national implosion, potentially followed by a planetary implosion. But Georgescu thinks that business leaders can fix this problem; I think he is hopelessly naive.

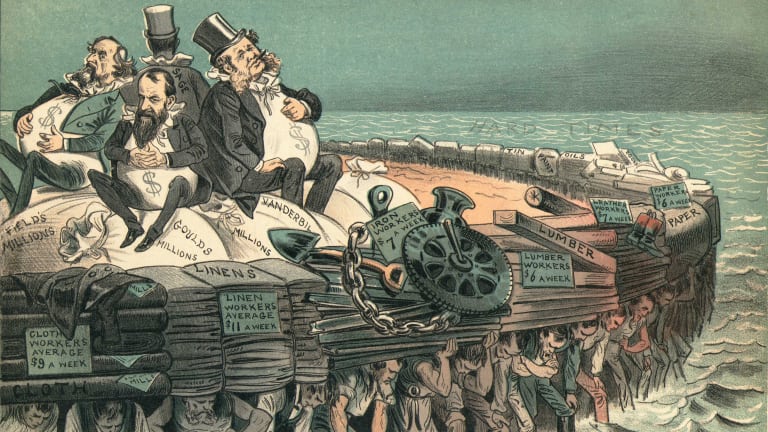

Georgescu may believe that the capitalism of the post World War II period was some kind of norm, but it wasn’t. Capitalism wasn’t a major factor in the U.S. economy until the mid-19th century, but from that time and until the Great Depression it was marked by its careless exploitation of workers and resources. It didn’t change into the generous and kindly capitallism Georgescu remembers until taken into hand by FDR’s New Deal. Paul Krugman wrote on his old New York Times blog,

The Long Gilded Age: Historians generally say that the Gilded Age gave way to the Progressive Era around 1900. In many important ways, though, the Gilded Age continued right through to the New Deal. As far as we can tell, income remained about as unequally distributed as it had been the late 19th century – or as it is today. Public policy did little to limit extremes of wealth and poverty, mainly because the political dominance of the elite remained intact; the politics of the era, in which working Americans were divided by racial, religious, and cultural issues, have recognizable parallels with modern politics.

The Great Compression: The middle-class society I grew up in didn’t evolve gradually or automatically. It was created, in a remarkably short period of time, by FDR and the New Deal. As the chart shows, income inequality declined drastically from the late 1930s to the mid 1940s, with the rich losing ground while working Americans saw unprecedented gains. Economic historians call what happened the Great Compression, and it’s a seminal episode in American history.

Middle class America: That’s the country I grew up in. It was a society without extremes of wealth or poverty, a society of broadly shared prosperity, partly because strong unions, a high minimum wage, and a progressive tax system helped limit inequality. It was also a society in which political bipartisanship meant something: in spite of all the turmoil of Vietnam and the civil rights movement, in spite of the sinister machinations of Nixon and his henchmen, it was an era in which Democrats and Republicans agreed on basic values and could cooperate across party lines.

The great divergence: Since the late 1970s the America I knew has unraveled. We’re no longer a middle-class society, in which the benefits of economic growth are widely shared: between 1979 and 2005 the real income of the median household rose only 13 percent, but the income of the richest 0.1% of Americans rose 296 percent.

And, of course, the late 1970s were all about the rise of “movement conservatism” and Reaganomics. And, in a lot of ways, we’re back to the Gilded Age. And it has to be acknowledged that this is what capitalism is without a whole lot of government interention to keep it honest.

The mistake most people make in looking at the financial crisis is thinking of it in terms of money, a habit that might lead you to look at the unfolding mess as a huge bonus-killing downer for the Wall Street class. But if you look at it in purely Machiavellian terms, what you see is a colossal power grab that threatens to turn the federal government into a kind of giant Enron – a huge, impenetrable black box filled with self-dealing insiders whose scheme is the securing of individual profits at the expense of an ocean of unwitting involuntary shareholders, previously known as taxpayers.

Yep. And that’s pretty much what happened.

The young folks think “capitalism” is a dirty word, and I don’t blame them. I hope that the future can be saved for them.

The young folks think “capitalism” is a dirty word, and I don’t blame them. I hope that the future can be saved for them.

Business leaders cannot be trusted to fix the mess they are making, even though a few of them see that it’s a mess and that it cannot continue indefinitely. Business never has fixed it in the past, and even now too many of them are happy to leave a dead planet to their grandchildren as long as they can make more money now. This cannot go on. If Republicans aren’t pried out of government in 2020 I despair that we will run out of time to prevent disaster.