I have a confession to make. Most of my ancestors came to America undocumented. They were without passports or even a green card, and they didn’t go through immigration processing.

That’s because most of ’em got here in the 18th century.

The ones we can document, anyway. Tracing the family tree backward through the generations, one sometimes hits a dead end. We’ll learn that William married Amanda in some Appalachian holler during the Andy Jackson administration but find no clue where Amanda came from or how long she and her folks had been here. My family were not exactly, um, aristocrats, so record-keeping was haphazard. But I do know that one branch can be traced back to some of the original Pennsylvania Dutch, arriving ca. 1710. Two of my great-times-four grandfathers fought in the Revolution. Generations of my foremothers bounced west on buckboards, gave birth in long cabins, and dug gardens in the virgin wilderness.

The latecomers included my mother’s mother’s grandparents, who arrived from Ireland shortly after the Civil War. And the absolute last guy off the boat was my father’s father’s father, William Thomas of Dwygyfylchi, Wales, who arrived ca. 1885. He married Minnie King, whose father Fielding King had marched through Georgia with General Sherman in a Missouri infantry volunteer regiment. We haven’t traced the generations of Kings back very far, however, so we have no idea when they came to America.

Anyway, this means none of them went through Ellis Island, which didn’t open for business until 1892. A few years ago, when Ellis Island became a national monument, the feds ran print ads with historic photos of Ellis Island immigrants. The captions claimed that the Ellis Island people “built America,” which pissed me off because that wasn’t true. By 1892 all of our major cities were already established; the intercontinental railroad was completed and running; the Midwestern fields cleared from the wilderness by my ancestors were well-tilled and filled with rows of corn. The Ellis Island people just filled the place in some, as far as I was concerned.

Well, OK, they filled it in a lot. Fifteen million immigrants arrived in America between 1890 and the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Earlier waves of immigrants had mostly come for the virtually free farmland, and they fanned out across the prairies and plains. But a large part of the fifteen million remained in cities and took factory jobs. They brought with them talent and industriousness but also crime and poverty and other problems that overwhelmed the cities. This in turn brought about a growth in government and a shifting of government programs from local to state to federal. For example, beginning in the 1910s the states, and eventually the feds, established “welfare” programs to relieve the destitution of immigrants; in earlier times, destitution had been dealt with by local “poor laws.”

Eventually they and their descendants assimilated to America, but it’s equally true that America assimilated to them. This is a very different country, physically and culturally, than it would have been had immigration been cut off in, say, 1886. The newcomers had not shared the experience of carving a nation out of the wilderness and fighting the Civil War. For a people often discriminated against, the Ellis Island-era immigrants were remarkably intolerant of African Americans and shut them out of the labor unions, making black poverty worse. And early state and federal welfare programs provided services only to whites. Immigrants literally took bread out of the mouths of the freedmen and their descendants, exacerbating racial economic disparities that we’re still struggling with today.

Much of American culture as it existed in the 1880s — the music, the folk tales, the way foods were cooked — was washed away in the flood of immigration and survived only in isolated places like rural Kentucky, where the descendants of colonial indentured servants still pretty much had the place to themselves. Here in the greater New York City area I am often dismayed at how much people don’t know about their own country. There are second- and third-generation Americans here who don’t know what a fruit cobbler is, for example. And as for knowing the words to “My Darling Clementine” or “Old Dan Tucker” — fuhgeddaboudit.

On the other hand, there are bagels. It’s a trade-off, I suppose.

I bring this up by way of explaining why I am bemused by some of the negative reactions to yesterday’s immigrant demonstrations. Yes, I realize there’s a distinction between legal and illegal immigrants nowadays. There is reason to be concerned about large numbers of unskilled workers flooding the job market and driving down wages — we learned a century ago that can be a problem. But the knee-jerk antipathy to all things Latino — often coming from newbies (to me, if you’re less than three generations into America, you’re a newbie) who aren’t fully assimilated themselves — is too pathetic. They’re worried about big waves of immigrants changing American culture? As we’d say back home in the Ozarks, ain’t no use closin’ the barn door now. Them cows is gone.

(I can’t tell you how much I’d love to confront Little Lulu and say, “Lordy, child, when did they let you in?”)

Near where my daughter lives in Manhattan there’s a church that was built by Irish immigrants. It is topped by a lovely Celtic cross. Now the parishioners are mostly Dominican. In forty years, if it’s still standing, maybe the priests will be saying masses in Cilubà , or Mandarin, or Quechuan. Stuff changes. That’s how the world is. That’s how America is, and how it always has been. Somehow, we all think that the “real” America is the one that existed when our ancestors got off the boat. That means your “real” America may be way different from mine. Fact is, if we could reconstitute Daniel Boone and show him around, he wouldn’t recognize this country at all. I think they had apple pie in his day, but much of traditional American culture — baseball, jazz, barbecue, John Philip Sousa’s “Stars and Stripes Forever” — didn’t exist in Daniel Boone’s “real” America.

Latinos, of course, already are American, and in large parts of the U.S. Latino culture had taken root before the Anglos showed up. This makes anti-Latino hysteria particularly absurd, because Latino culture is not new; it’s already part of our national cultural tapestry. And who the bleep cares if someone sings the national anthem in Spanish? As Thomas Jefferson said in a different context, it neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg. I’m sure the anthem has been sung in many languages over the years, because the U.S. has always been a multilingual nation. Along with the several native languages, a big chunk of the 19th-century European farmers who fanned out across the prairies and plains lived in communities of people from the same country-of-origin so they didn’t have to bother to learn English. And many of them never did. It’s a fact that in the 19th century, in many parts of the U.S., German was more commonly spoken than English.

Yes, maybe someday America will be an officially bilingual nation, and maybe someday flan will replace apple pie. Flan is good, and there are many multilingual nations that somehow manage to make it work — India, China, Belgium, and Switzerland come to mind. Even much of my great-grandpa’s native Wales stubbornly persists in speaking Welsh. Multilingualism doesn’t have to be divisive unless bigotry makes it so.

What’s essential to the real America — our love of liberty — is the only constant. And, frankly, it’s not illegal immigrants who are a threat to liberty.

I want to thank alert reader Jim Murphy for sending this photo. What a hoot. Does the Weenie think he’s really fooling anybody?

I want to thank alert reader Jim Murphy for sending this photo. What a hoot. Does the Weenie think he’s really fooling anybody?

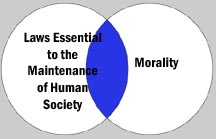

The realm of morality, however, is separate from the realm of legality. There are all manner of things that we might consider immoral that are not, in fact, illegal; adultery is a good example. Such acts may have harmful personal consequences, but regulating them isn’t necessary to civilization. And I don’t see what’s immoral about, say, misjudging how many coins you should put in the parking meter. That’s why I tend to see the legal versus moral question on a Venn diagram. The diagram here isn’t entirely accurate since the blue area should be bigger — law and morality intersect more often than they don’t. I’m just saying that answering the moral question of abortion (assuming we ever will) does not tell us whether an act should be legal or not. In fact, since abortion is legal (with varying restrictions) in most democratic nations today with no discernible damage to civilization itself, I’d say the abortion question falls outside the blue area of the diagram.

The realm of morality, however, is separate from the realm of legality. There are all manner of things that we might consider immoral that are not, in fact, illegal; adultery is a good example. Such acts may have harmful personal consequences, but regulating them isn’t necessary to civilization. And I don’t see what’s immoral about, say, misjudging how many coins you should put in the parking meter. That’s why I tend to see the legal versus moral question on a Venn diagram. The diagram here isn’t entirely accurate since the blue area should be bigger — law and morality intersect more often than they don’t. I’m just saying that answering the moral question of abortion (assuming we ever will) does not tell us whether an act should be legal or not. In fact, since abortion is legal (with varying restrictions) in most democratic nations today with no discernible damage to civilization itself, I’d say the abortion question falls outside the blue area of the diagram.