Quick follow up to yesterday’s Armistice Day post — I’ve been wondering how many World War I vets were still alive. Here’s the answer: one.

At ease, soldiers.

Quick follow up to yesterday’s Armistice Day post — I’ve been wondering how many World War I vets were still alive. Here’s the answer: one.

At ease, soldiers.

Today the Keyboarding Vegetable makes excuses for Ronald Reagan:

The distortion concerns a speech Ronald Reagan gave during the 1980 campaign in Philadelphia, Miss., which is where three civil rights workers had been murdered 16 years earlier. An increasing number of left-wing commentators assert that Reagan kicked off his 1980 presidential campaign with a states’ rights speech in Philadelphia to send a signal to white racists that he was on their side. The speech is taken as proof that the Republican majority was built on racism.

The truth is more complicated.

Of course it is. For example, one little tidbit that Brooks left out is that this same Philadelphia, Mississippi, was already infamous as a place where three civil rights activists were murdered.

I’ve already explained here that “states’ rights” was universally recognized as code for “white supremacy” back in those days. If Reagan didn’t understand what message he was sending, then he was an idiot. You know how upset righties get when you say Reagan was an idiot. And, truly, he was a genius compared to George Bush.

And the moral is: Context is everything.

Instaputz and Bark Bark Woof Woof nicely take down Brooks in more detail. I just want to add one more point to what they’ve written.

I realize it is possible nowadays to favor stronger state sovereignty on principle without being a racist. But Jim Crow and states rights’ were so tightly woven together back in the day that a politician who didn’t want to send winks and nudges to white racists would never have used the phrase “states rights.” I might understand how someone (especially someone not old enough to appreciate the, um, nuances of the times) might be persuaded to think that the Philadelphia speech was just a misstep. But as Paul Krugman wrote of another apologist,

Bruce Bartlett’s attempt to explain away Reagan’s Philadelphia speech as an innocent misunderstanding would be more plausible if it were out of character for Reagan’s career. But tacit appeals to racial politics — often taking the form of tall stories about welfare cheats, culminating in the Cadillac-driving welfare queen — were, in fact, a staple of Reagan’s political career.

Two issues were critical to the Reagan landslide in 1980. One was Iran, and the other was the Cadillac Queen. Iran probably got more media coverage, but IMO it was Reagan’s stories about the Cadillac Queen that won the deal. During the 1980 campaign I can’t tell you how many times I overheard whites say “I’m voting for Reagan because he’s going to kick the n—— off welfare.”

So don’t bother arguing with me that Reagan didn’t run on an appeal to racism. I watched him do exactly that.

Regarding all the weeping and wailing from the Right over recent comments by Rep. Pete Stark, I agree with Digby that their outrage seems a tad calculated.

Are these macho tough guys really offended that some congressman made these comments in a debate? Are their feelings hurt on behalf of the president? Does CNN really believe that’s what’s going on? Does anyone think that what Pete Stark said on the floor yesterday truly upset the Republicans? Of course not. These are the same people who spent month after month calling president Clinton a rapist and worse, for crying out loud. They are not shrinking violets who believe that there are limits to acceptable rhetoric about the president. They don’t believe there are limits to any rhetoric.

Everyone knows exactly why the Republicans sent out “statement after statement” about this obscure congressman’s words yesterday — distraction. Does anyone point that out? No. In fact, the damned Democrats go right along with this nonsense and “hold meetings” and leak to the press about how they agree with the Republicans agreeing that Stark caused the distraction, and basically showing themselves to be a bunch of pathetic fumblers falling for this nonsense over and over again.

For the record, here’s what Congressman Stark said:

“I’m just amazed that the Republicans are worried that we can’t pay for insuring an additional 10 million children. They sure don’t care about finding $200 billion to fight the illegal War in Iraq.

“Where are you going to get that money? You’re going to tell us lies like you’re telling us today? Is that how you’re going to fund the war? You don’t have money to fund the war or children.

“But you’re going to spend it to blow up innocent people if we can get enough kids to grow old enough for you to send to Iraq to get their heads blown off for the President’s amusement.

“This bill would provide health care for 10 million children and unlike the President’s own kids, these children can’t see a doctor or receive necessary care.

“Six million are insured through the Children’s Health Insurance Program and they’ll do better in school and in life.

“In California, the President’s veto will cause the legislature to draw up emergency regulations to cut some 800,000 children off the rolls in California and create a waiting list. I hope my California Republican colleagues will understand that if they don’t vote to override this veto, they are destroying health care for many of our children in California.

“In his previous job as an actor, our Governor used to play make believe and blow things up. Well, the President and Republicans in Congress are playing make believe today with children’s lives.

“They claim we can’t afford health care and say the bill will socialize Medicine. Tell that to Orrin Hatch, Chuck Grassley, and Ted Stevens, those socialists on the other side of this Capitol! The truth is that the Children’s Health Insurance Program enables states to cover children primarily through private health care plans.

“President Bush’s statements about children’s health shouldn’t be taken any more seriously than his lies about the War in Iraq. The truth is that that Bush just likes to blow things up – in Iraq, in the United States, and in Congress.

“I urge my colleagues to vote to override his veto. America’s children need and deserve health care despite the President’s desire to deny it to them.”

Here’s the video:

[Update: From the “lies and the lying liars who tell them” department — rightie blog Gateway Pundit accuses Crooks and Liars of misquoting Stark. But Gateway Pundit lies. C&L quoted Stark accurately. What Gateway Pundit quotes as the “accurate” statement is a different part of the same statement. Gateway Pundit also called Stark’s statement “anti-military,” and I believe that is a lie; I don’t see anything anti-military about it.]

Is that really so outrageous? Maybe the line about “kids to grow old enough for you to send to Iraq to get their heads blown off for the President’s amusement” was hyperbole, if only because Bush might have noticed that soldiers are getting tougher to replace. But the rest of it seems fairly mild. I know I could have come up with something a lot harsher.

The double standard about what one can say about a President has been going on for a long time. I was a teenager during the LBJ years, and I doubt any president ever got slammed harder than Johnson did. And that was by the press, the public, and other politicians across the board. I can’t say he didn’t deserve it. Maybe I missed it, but I don’t remember that anyone complained much that a president ought to be treated with more decorum, if only out of respect for the office.

But that changed during the Nixon years. Television reports of criticism of Nixon frequently were “balanced” by expressions of outrage that anyone would say such things about a President of the United States. No end of sweet-faced matrons, tears in their eyes and quivers on their lips, expressed shock that anyone would talk about a President so. Burly men with VFW caps pounded tables and thundered, they’re saying these things about the President, as if public criticism of a President were somehow beyond the pale of civilized conduct. Never mind that most of “these things” turned out to be true, and never mind that Johnson was treated, IMO, much worse than Nixon was, at least by the standards of Nixon’s first term. The Watergate scandal did let the dogs loose, so to speak.

President Ford was ridiculed frequently, and my impression is that the Right didn’t exactly have his back. True righties didn’t care for Ford, possibly because they truly despised his Vice President, Nelson Rockefeller. President Carter also was ridiculed mercilessly through his presidency.

But after Saint Ronald was elected, suddenly conservatives became very protective of the dignity of the office. And the White House press corps of the Reagan Administration was a muzzled and castrated thing compared to that of the Johnson years. Something had changed.

And as soon as Bill Clinton was elected, it was open season on Presidents again.

There’s no doubt in my mind that this shifting of of standards is being orchestrated from the top of the rightie power pyramid. But I don’t think rank-and-file righties are capable of seeing the double standard as a double standard. In their minds, the only legitimate presidents are the conservative ones, and the rest are interlopers, never mind that they were elected.

But that takes us to another question, and let’s keep it hypothetical. Let’s say frank, harsh criticism of a head of state is unacceptable and cause for public censure, unless the head of state is a tyrant. We tend to think that people who stand up to a tyrant are being courageous and heroic. Where is the line drawn? A remark that seems unfair to the head of state’s supporters might seem perfectly fair to lots of other people. At what point does the needle flip from “not OK” to “OK”?

I say it’s not always clear, particularly in the case of an up-and-coming tyrant who hasn’t yet gained full dictatorial powers. Early in their political careers even the great tyrants of history — Mao, Hitler, Stalin — didn’t seem that bad to everyone.

My questions:

Are people supposed to keep their mouths shut until after freedom of speech has been lost?

If people are intimidated by societal pressure from speaking frankly about a moderate, democratic leader, how will they find the courage to speak out when the real tyrant shows up?

Every president is slammed by some part of the public, including members of Congress who are, after all, representing the people. I don’t agree that Congress critters have to hold their tongues out of some sense of beltway propriety. They’re supposed to be speaking for us. If our representatives can’t speak frankly, who will?

If the criticism is genuinely off the wall, it’s fair to criticize it back. If someone makes false accusations about a President, by all means speak up loudly and set the record straight. Let the court of public opinion judge the matter. But let’s stop playing games about what commentary is appropriate or disrespectful of the office. I say that if a citizen, politician or otherwise, is thinking something, he shouldn’t be afraid to say it.

You must read this Washington Post article about a group of World War II veterans who were interrogators of Nazi prisoners. Petula Dvorak writes,

When about two dozen veterans got together yesterday for the first time since the 1940s, many of the proud men lamented the chasm between the way they conducted interrogations during the war and the harsh measures used today in questioning terrorism suspects.

Back then, they and their commanders wrestled with the morality of bugging prisoners’ cells with listening devices. They felt bad about censoring letters. They took prisoners out for steak dinners to soften them up. They played games with them.

“We got more information out of a German general with a game of chess or Ping-Pong than they do today, with their torture,” said Henry Kolm, 90, an MIT physicist who had been assigned to play chess in Germany with Hitler’s deputy, Rudolf Hess.

Blunt criticism of modern enemy interrogations was a common refrain at the ceremonies held beside the Potomac River near Alexandria. Across the river, President Bush defended his administration’s methods of detaining and questioning terrorism suspects during an Oval Office appearance.

Several of the veterans, all men in their 80s and 90s, denounced the controversial techniques. And when the time came for them to accept honors from the Army’s Freedom Team Salute, one veteran refused, citing his opposition to the war in Iraq and procedures that have been used at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba.

“I feel like the military is using us to say, ‘We did spooky stuff then, so it’s okay to do it now,’ ” said Arno Mayer, 81, a professor of European history at Princeton University.

When Peter Weiss, 82, went up to receive his award, he commandeered the microphone and gave his piece.

“I am deeply honored to be here, but I want to make it clear that my presence here is not in support of the current war,” said Weiss, chairman of the Lawyers’ Committee on Nuclear Policy and a human rights and trademark lawyer in New York City. …

…”We did it with a certain amount of respect and justice,” said John Gunther Dean, 81, who became a career Foreign Service officer and ambassador to Denmark.

“During the many interrogations, I never laid hands on anyone,” said George Frenkel, 87, of Kensington. “We extracted information in a battle of the wits. I’m proud to say I never compromised my humanity.”

If you’re a history buff, you’ll want to read the whole thing. Fascinating stuff. And you’d think any supporter of Bush’s interrogation “methods” would feel ashamed, wouldn’t you?

Well, forget that. Apparently the World War II guys didn’t have to rely on torture because they were dealing with a better class of people than interrogators must handle today.

That’s right. Nazis were nicer. Captain Ed explains,

It must be said, however, that they faced a different enemy in a different war. The Germans fought to expand territory through traditional warfare, at least as arrayed against the US and the West. While they conducted sabotage missions in the US through espionage, they did not use terrorist infiltrators to attempt to kill thousands of American civilians. They also did not face religious extremists who believed that death brought them to Allah and 72 waiting virgins for taking out women and children. One can make a case that the civilized techniques of PO Box 1142 worked because their detainees also believed themselves civilized and members of the Western culture.

More civilized? Um, the Holocaust? Ring any bells?

The eternally dim Sister Toldjah asked,

Does the Post believe interrogators would have gotten the same information from Khalid Sheikh Mohammed by taking him out to a steak dinner and/or playing games with him instead of waterboarding him (an aggressive interrogation tactic which, btw, saved lives)?

Of course, it’s possible interrogators would have gotten different information had KSM not been tortured. They might have, for example, gotten accurate information.

Yesterday on Countdown, Keith Olbermann interviewed former CIA Case Officer Robert Baer about this New York Times article on secret “interrogation” methods. I can’t figure out how to link to the MSNBC video directly, but you can find it on the Countdown page; click on “Bush’s Torture Woes.” Here’s a transcript I made from the video:

BAER: Keith, I’ve spent 21 years in the Middle East working for the CIA, I’ve seen the results of torture, in countries from Egypt to Syria to Saudi Arabia, and the intelligence is dribble. It leads to false leads. People will say anything if the pain is bad enough. It is useless, and I reiterate it is useless. I’ve spent three years now visiting Israeli jails talking to Hamas prisoners, talking to Shin Bet, their intelligence service, and they agree it’s useless. They use traditional police techniques, interrogations, legal interrogations, and they get more out of an investigation than torture.

OLBERMANN: As a professional and an experienced researcher now, I imagine something in the Times story yesterday might have been the most disturbing thing here, just on a professional, what in the world are they doing level, to you, the case of Mohammed, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who was severely interrogated over a period of about two weeks, but the problem was as the Times put it, the initial interrogators were not experts on Mr. Mohammed’s background or al Qaeda. Instead of beating him up, does it shock you that the agency could have been much more easily served by having some guy who knew what the hell he was talking about and ask him questions? Because, obviously, a lot of these statements proved to be wildly false, and as you said produced extraordinarily misleading lines of inquiry and perhaps, who knows what else, besides inquiry.

BAER: We know that he lied about his participation in the murder of Danny Pearl, the Wall Street Journal journalist who was killed in Pakistan, his head cut off. He just made that up, that he wielded the knife. He did that under torture. The problem I have is that if he’s our main source of information on what happened on 9/11, and it was extracted by torture, which everyone will tell you is unreliable, I’m not quite sure what happened on 9/11. We’re just adding conspiracy theories when we get information like this, and that’s not to mention that we’re trying to win the hearts and minds of people in the Middle East, but that’s a moral question that someone should answer.

Once the Bushies are pried out of the White House it may take us years to unravel what’s real and what isn’t.

Finally, that wart on the buttocks of humanity known as Jules Crittendon doesn’t even bother making excuses. He just goes right into ridicule mode. But adds —

[T]he apparently genteel program at Fort Hood doesn’t represent the totality of Allied practices re captured enemies in World War II, which though famously a “good war†also included summary executions of Japanese prisoners. After they and/or their comrades were found to have tortured Americans to death.

— which exemplifies the problem, I think. Righties cannot separate vengeance from interrogation. They defend torture not because it’s useful, but because it’s gratifying.

Update: This is sortakinda related — “I Survived Blackwater.”

I may be numerically challenged, but I can read a table. A rightie blogger claimed,

Did you know that more members of the military were killed in Jimmy Carter’s last year in the White House than in any of the years we’ve been fighting in Iraq? Think about that. In the peaceful year of 1980, 2,392 servicemen died while on duty defending our country. In 2003, the start of the Iraq War, only 1,228 servicemen and women died. In 2004, the number was 1,874, it went up to 1,942 in 2005, and it dropped to 1,858 in 2006.

WTF? You say. The blogger is pulling these numbers from page 10, Table 5, of this PDF document. In 1980, out of a total of 2,159,630 persons in the military (active and reserve), 2,392 died. In 2006, out of a total of 1,664,014 persons in the military, 1,858 died.

I bet you see where this post is going already.

As a commenter helpfully pointed out, the military was 50 percent bigger in 1980 than it is now. In 1980, the commenter calculated, there were 1.17 deaths per 1000 soldiers. By 2000, the fatality rate had dropped to 0.55 per 1000 soldiers. We can see from Table 5 on page 11 of the same document that a reduction in the rate of accidents lowered the overall fatality rate. In 2006, however, there were 1.35 deaths per 1000 soldiers.

We can also see that in 1980 there were zero deaths from hostile action and one from a terrorist attack. I don’t know what happened to the one. In 2006, there were 753 deaths from hostile action and 238 deaths pending determination of cause.

Also note that the tables don’t say if the military personnel were on duty or on leave or enjoying free time when they died.

Back to the rightie blogger:

In fact, only during the Clinton years of 1996 into the Bush years of 2001 and 2002, during a period of time when the Clinton policy of refusing to defend our national interest was in place, do we see the number of military deaths fall below 1000 annually.

During the 1980’s, when we aggressively defended the peace against the Soviets, the number of military deaths routinely topped 2000, with a high in 1983, the year of the Marine barracks bombing in Lebanon, topping out at 2,465.

The number of active-duty military personnel dropped quite a bit in the 1990s. It went from 2,046,806 in 1990 to 1,367,838 in 1999. The number of selected reserve troops also decreased in the 1990s, although the number of national guard remained steady. Fewer troops, fewer deaths.

During the entire decade of the 1980s, a total of 81 troops died in hostile action and 294 died in terrorist attacks (263 in 1983). The rest died of accidents, illness, and homicides.

But let’s go back to the key point, more members of the military died in 1980, while Jimmy Carter was in the White House abdicating our responsibilities around the world, than in any one of the years we’ve been in Iraq.

The moral of the story is that peace is dangerous.

I’d say the moral is that somebody is dumb as a bag of hammers.

Update: Somebody at the Weekly Standard can’t read tables, either.

Via Hilzoy, Peter Beinart writes about his early support for the Iraq invasion.

“I was willing to gamble, too–partly, I suppose, because, in the era of the all-volunteer military, I wasn’t gambling with my own life. And partly because I didn’t think I was gambling many of my countrymen’s. I had come of age in that surreal period between Panama and Afghanistan, when the United States won wars easily and those wars benefited the people on whose soil they were fought. It’s a truism that American intellectuals have long been seduced by revolution. In the 1930s, some grew intoxicated with the revolutionary potential of the Soviet Union. In the 1960s, some felt the same way about Cuba. In the 1990s, I grew intoxicated with the revolutionary potential of the United States.

Some non-Americans did, too. “All the Iraqi democratic voices that still exist, all the leaders and potential leaders who still survive,” wrote Salman Rushdie in November 2002, “are asking, even pleading for the proposed regime change. Will the American and European left make the mistake of being so eager to oppose Bush that they end up seeming to back Saddam Hussein?”

I couldn’t answer that then. It seemed irrefutable. But there was an answer, and it was the one I heard from that South African many years ago. It begins with a painful realization about the United States: We can’t be the country those Iraqis wanted us to be. We lack the wisdom and the virtue to remake the world through preventive war. That’s why a liberal international order, like a liberal domestic one, restrains the use of force–because it assumes that no nation is governed by angels, including our own. And it’s why liberals must be anti-utopian, because the United States cannot be a benign power and a messianic one at the same time. That’s not to say the United States can never intervene to stop aggression or genocide. It’s not even to say that we can’t, in favorable circumstances and with enormous effort, help build democracy once we’re there. But it does mean that, when our fellow democracies largely oppose a war–as they did in Vietnam and Iraq–because they think we’re deluding ourselves about either our capacities or our motives, they’re probably right. Being a liberal, as opposed to a neoconservative, means recognizing that the United States has no monopoly on insight or righteousness. Some Iraqis might have been desperate enough to trust the United States with unconstrained power. But we shouldn’t have trusted ourselves.”

Hilzoy adds, wisely, “It’s not just that we aren’t the country Beinart wanted to think we were; it’s that war is not the instrument he thought it was.” I suggest reading Hilzoy’s post all the way through; it’s very good.

But I want to go on to another thought here. Yesterday I wrote about nonviolent resistance and quoted from an article in the Spring 2007 issue of the American Buddhist magazine Tricycle — available to subscribers only — called “The Disappearance of the Spiritual Thinker†by Pankaj Mishra. It begins:

“I NEVER KNEW A MAN,†Graham Greene famously wrote in The Quiet American, “who had better motives for all the trouble he caused.†After the disaster in Iraq, Greene’s 1955 description of an idealistic American intellectual blundering through Vietnam seems increasingly prescient. People shaped entirely by book learning and enthralled by intellectual abstractions such as “democracy†and “nation-building†are already threatening to make the new century as bloody as the previous one.

It is too easy to blame millenarian Christianity for the ideological fanaticism that led powerful men in the Bush administration to try to remake the reality of the Middle East. But many liberal intellectuals and human rights activists also supported the invasion of Iraq, justifying violence as a means to liberation for the Iraqi people. How did the best and the brightest–people from Ivy League universities, big corporations, Wall Street, and the media–end up inflicting, despite their best intentions, violence and suffering on millions? Three decades after David Halberstam posed this question in his best-selling book on the origins of the Vietnam War, The Best and the Brightest, it continues to be urgently relevant: Why does the modern intellectual–a person devoted as much professionally as temperamentally to the life of the mind–so often become, as Albert Camus wrote, “the servant of hatred and oppressionâ€? What is it about the intellectual life of the modern world that causes it to produce a kind of knowledge so conspicuously devoid of wisdom?

What is it about the intellectual life of the modern world that causes it to produce a kind of knowledge so conspicuously devoid of wisdom? Wow, that’s a question, isn’t it? Where do overeducated twits like Doug Feith and Paul Wolfowitz and Condi Rice come from, and how the hell did they get put in charge of foreign policy? They may be articulate, and they have Ph.D.s and impressive resumes, but they don’t have the sense God gave onions.

THE POWER OF secular ideas–and of the men espousing them–was first highlighted by the revolutions in Europe and America and the colonization of vast tracts of Asia and Africa, and then with Communist social engineering in Russia and China. These great and often bloody efforts to remake entire societies and cultures were led by intellectuals with passionately held conceptions of the good life; they possessed clear-cut theories of what state and society should mean; and in place of traditional religion, which they had already debunked, they were inspired by a new self-motivating religion: a belief in the power of “history.â€

It took two world wars, totalitarianism, and the Holocaust for many European thinkers to see how the truly extraordinary violence of the twentieth century–what Camus called the “slave camps under the flag of freedom, massacres justified by philanthropy‖derived from a purely historical mode of reasoning, which made the unpredictable realm of human affairs appear as amenable to manipulation as a block of wood is to a carpenter.

Shocked like many European intellectuals by the mindless slaughter of the First World War, the French poet Paul Valéry dismissed as absurd the many books that had been written entitled “the lesson of this, the teaching of that†and that presumed to show the way to the future. The Thousand-Year Reich, which collapsed after twelve years, ought to have buried the fantasy of human control over history. But advances in technological warfare strengthened the conceit, especially among the biggest victors of the Second World War, that they were “history’s actors†and, as a senior adviser to President Bush told the journalist Ron Suskind in 2004, that “when we act we create our own reality.â€

These are the same people who have pathological confidence in themselves, of course. As Peter Birkenhead wrote, “Pumped up by steroidic pseudo-confidence and anesthetized by doubt-free sentimentality, they are incapable of feeling anything authentic and experiencing the world.” Perhaps its a class thing; perhaps these are people who have lived lives so buffered from failure and the consequences of misjudgments that they never learned a healthy respect for failure and the consequences of misjudgments.

History as an aid to the evolution of the human race seems to be most fully worked out by the respected Harvard historian Niall Ferguson. Writing in the New York Times Magazine a few weeks after the invasion of Iraq, Ferguson declared himself a “fully paid-up member of the neo-imperialist gang,†and asserted that the United States should own up to its imperial responsibilities and provide in places like Afghanistan and Iraq “the sort of enlightened foreign administration once provided by self-confident Englishmen in jodhpurs and pith helmets.†In his recent book Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire (2004), Ferguson argues that “many parts of the world would benefit from a period of American rule.â€

Ferguson has a regular column at the Los Angeles Times. And he’s a classic overeducated twit.

But back to Pankaj Mishra:

IT IS HARD TO IMAGINE now how this all began, how, in the nineteenth century, the concept of history acquired its significance and prestige. This was not history as the first great historians Herodotus and Thucydides had seen it: as a record of events worth remembering or commemorating. After a period of extraordinary dynamism in the nineteenth century, many people in Western Europe–not just Hegel and Marx–concluded that history was a way of charting humanity’s progress to a higher state of evolution.

In its developed form the ideology of history described a rational process whose specific laws could be known and mastered just as accurately as processes in the natural sciences. Backward natives in colonized societies could be persuaded or forced to duplicate this process; and the noble end of progress justified the sometimes dubious means–such as colonial wars and massacres.

Pankaj Mishra is arguing that this view of history is a kind of secular thinking, and it is, but not purely so. I’ve been reading Mark Lilla’s book The Stillborn God: Religion, Politics and the Modern West. I blogged about this book here and here. Very briefly, Lilla writes about the nexus of politics and religion in western civilization, particularly since the end of the Reformation and the publication of Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan. I’m not all the way through it yet. But he seems to be building an argument that messianic religion as a habit of mind continually re-asserts itself and seeps into secular thought. So we have public intellectuals who may or may not be followers of religion or believers in God, but who still think in messianic terms. However, instead of looking forward to the Second Coming, secular messianic thought sees history building toward some politically and economically ideal future as if compelled by natural law.

Some might argue that any kind of messianic thought is religious, but defining religion that way would make Christopher Hitchens the bleeping pope.

Lilla’s book suffers a bit from a narrow understanding of religion, IMO. But perhaps that’s me. As I wrote a couple of days ago, east Asian religions as a rule think of time and events, cause and effect, as circular rather than linear. The revered Zen master Dogen Zenji (1200-1250) presents linear time as a kind of delusion; see Uji. If you don’t perceive time and history as linear it’s hard to be messianic. However, as I’ve said elsewhere, certainly Asia has seen its share of mass movements bent on shaping history — China under Mao comes to mind.

Pankaj Mishra continues,

This instrumental view of humanity, which Communist regimes took to a new extreme with their bloody purges and gulags, couldn’t be further from the Buddhist notion that only wholesome methods can lead to truly wholesome ends. It is in direct conflict with the notion of nirvana, the end of suffering, a goal many secular and modern intellectuals purport to share, but which can only be achieved through the extinction of attachment, hatred, and delusion.

Indeed, no major traditions of Asia or Africa accommodate the notion that history is a meaningful narrative shaped by human beings. Time, in fact, is rarely conceptualized as linear progression in many Asian and African cultures; rather, it is custom and religion that circumscribe human interventions in the world. Buddhism, for instance, in its emphasis on compassion and interdependence, is innately inhospitable to the Promethean spirit of self-aggrandizement and conquest that has shaped the new “historical†view of human prowess. This was partly true also for many European cultures until the modern era, when scientific and technological innovations began to foster the belief that man’s natural and social environment was to be subject to rational manipulation and that history itself, no longer seen as a neutral, objective narrative, could be shaped by the will and action of man.

It was this faith in rational manipulation that powered the political, scientific, and technological revolutions of the West in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries; it was also used to explain and justify Western domination of the world–a fact that gave conviction to such words as progress and history (as much ideological buzzwords of the nineteenth century as democracy and globalization are of the present moment).

Now we circle back to Peter Beinart and other prominent “public intellectuals”:

The great material and technological success of the West, and the growth of mass literacy and higher education, produced its own model of the secular thinker: someone trained, usually in academia, in logical thinking and possessed of a great number of historical facts. No moral or spiritual distinction was considered necessary for this thinker; not more than technical expertise was asked of the scientists who helped create the nuclear weapons that could destroy the world many times over.

I should note, to be fair, that Robert Oppenheimer had studied eastern religion, particularly Hindu.

IT IS STRANGE TO THINK how quickly the figure of the spiritually-minded thinker disappeared from the mainstream of the modern West, to live on precariously in underdeveloped societies like India. It was left to marginal religious figures such as Simone Weil, Reinhold Niebuhr, and Thomas Merton to exercise a moral and spiritual intelligence untrammeled by the conviction that science or socialism or free trade or democracy were helping mankind march to a historically predetermined and glorious future. But then, as Hannah Arendt wrote, “The nineteenth century’s obsession with history and commitment to ideology still looms so large in the political thinking of our times that we are inclined to regard entirely free thinking, which employs neither history nor coercive logic as crutches, as having no authority over us.†[emphasis added]

We don’t often think of history as a crutch. Maybe we’ve become a little too obsessed with remembering history so we don’t repeat it. Since the invasion of Iraq we’ve argued whether Iraq is World War II or Vietnam or some other historical relic rattling around in our national attic. What we don’t do so much is try to understand Iraq as Iraq. Of course, we don’t remember our history as-it-was, either, but as we want to believe it was.

In America, religious and political ideology have always been interconnected, but in recent years we’ve taken this interconnection to absurd degrees. For example, the above-mentioned Niall Ferguson argues that America is more productive than Europe because our workers go to church more often than their workers. This begs the question — why is productivity a more “religious” virtue than, say, spending more time away from work to be with family? I think what we’re really seeing here is less about religion and more about voluntary submission to the authority of churches and employers.

But don’t hold your breath waiting for a public intellectual like Ferguson to make that connection. That requires thinking outside the box, and our public intellectuals are like a priestly caste charged with maintaining and protecting the box.

Peter Beinart may be trying, however. “[L]iberals must be anti-utopian, because the United States cannot be a benign power and a messianic one at the same time,” he said. Exactly. But we’ve got a job ahead of us explaining that to the rest of America.

Believe it or not, Michael Medved has a column at Townhall making excuses for slavery in America. It wasn’t all that bad, he says.

Medved presents six “inconvenient truths” about slavery, which (condensed) are:

1. American didn’t invent slavery. Lots of other countries did it too. Yes, but by the mid-19th century the practice had been pretty much run out of Europe, as well as the northern states, for being barbaric and immoral.

2. Slavery existed only briefly — 89 years from the Declaration of Independence to the 13th Amendment. It probably didn’t seem all that brief to the persons who were enslaved. And, of course, it had been going on for some time before the Declaration of Independence. Medved figures that only about 5 percent of today’s Americans are the descendants of slave owners. That may or may not be true, but I’m not sure why it’s relevant to anything.

3. Slavery wasn’t genocidal. Dead slaves brought no profit, Medved says. Of course, about a third of the people captured in Africa to be sold into slavery died in the ship voyage to America, but Medved says the slavers didn’t intend the slaves to die, so it doesn’t count. “And as with their horses and cows, slave owners took pride and care in breeding as many new slaves as possible,” Medved writes. No, really, he actually wrote that. I am not making this up.

4. It is not true that the United States became wealthy through slave labor, Medved says. Many “free soil” states were more prosperous overall than the slave states. That may be true, or not, but those cotton plantations were cash cows for the plantation owners. In 1855 raw cotton amounted to one-half of all U.S. exports, valuing $100 million annually in 1855 dollars. (Source: Encyclopedia of American Facts & Dates [Harper & Row, 1987] p. 255.) There was huge income disparity in the slave states; the plantation-owning elite hoarded the wealth.

5. The United States deserves special credit for abolition. Huh?

6. “There is no reason to believe today’s African-Americans would be better off if their ancestors had remained in Africa. ” Actual quote. Who says conservatives are insensitive? Well, me, for one.

Jillian at Sadly, No and John Holbo at Crooked Timber also comment. But no one so far has asked the critical question, which is What the hell was eating at Medved’s reptilian brain that inspired him to write this? Has criticism of American slavery been in the news lately?

Update: See also Kevin at Lean Left, who has a more substantive retort to “fact” #5 than I did.

Year the British ended slavery throughout the Empire: 1833. Number of wars it took to do so: 0. Year the Spanish Empire ended slavery (except in Cuba, where the ban was not enforced by local governors until 1886): 1811. Number of wars to do so: 0. Year the U.S. ended slavery throughout the country and its territories: 1865. Number of wars it took to do it: 1, the bloodiest one in American history. In fact, all European powers abolished slavery before the United States did. So, no, dear Mr. Medved, we as a nation don’t deserve special credit for a bloody damn thing. We were below average, even by the standards of the day.

Update 2: I’d like to add that during our civil war the wealthy industrial interests of Britain put a lot of pressure on Victoria and Parliament to enter the war on the side of the Confederacy. The Americas were their chief supplier of raw materials for their textile mills, and the owners were losing money. But anti-slavery sentiment was so strong in Britain — even among mill workers who’d been laid off because of the war — that active support for the Confederacy was out of the question. And, of course, Prince Albert favored the Union, which means Victoria did, also.

Update 3: This is a riot.

I’m so happy the New York Times got rid of that damnfool subscription firewall. Now I can link directly to Bob Herbert’s excellent column today.

“The G.O.P. has spent the last 40 years insulting, disenfranchising and otherwise stomping on the interests of black Americans,” he writes. Last week the Senate Republicans blocked the vote on a measure that would have given District of Columbia residents — who are mostly black — representation in Congress. And then there was the debate snub —

At the same time that the Republicans were killing Congressional representation for D.C. residents, the major G.O.P. candidates for president were offering a collective slap in the face to black voters nationally by refusing to participate in a long-scheduled, nationally televised debate focusing on issues important to minorities.

The radio and television personality Tavis Smiley worked for a year to have a pair of these debates televised on PBS, one for the Democratic candidates and the other for the Republicans. The Democratic debate was held in June, and all the major candidates participated.

The Republican debate is scheduled for Thursday. But Rudy Giuliani, John McCain, Mitt Romney and Fred Thompson have all told Mr. Smiley: “No way, baby.â€

They won’t be there. They can’t be bothered debating issues that might be of interest to black Americans. After all, they’re Republicans.

This is the party of the Southern strategy — the party that ran, like panting dogs, after the votes of segregationist whites who were repelled by the very idea of giving equal treatment to blacks. Ronald Reagan, George H.W. (Willie Horton) Bush, George W. (Compassionate Conservative) Bush — they all ran with that lousy pack.

Here’s something about Saint Ronald of Blessed Memory they’d rather we all forgot:

Dr. Carolyn Goodman, a woman I was privileged to call a friend, died last month at the age of 91. She was the mother of Andrew Goodman, one of the three young civil rights activists shot to death by rabid racists near Philadelphia, Miss., in 1964.

Dr. Goodman, one of the most decent people I have ever known, carried the ache of that loss with her every day of her life.

In one of the vilest moves in modern presidential politics, Ronald Reagan, the ultimate hero of this latter-day Republican Party, went out of his way to kick off his general election campaign in 1980 in that very same Philadelphia, Miss. He was not there to send the message that he stood solidly for the values of Andrew Goodman. He was there to assure the bigots that he was with them.

“I believe in states’ rights,†said Mr. Reagan. The crowd roared.

Let’s talk about states’ rights. Juan Williams writes at the Washington Post:

Fifty years ago this week, President Dwight Eisenhower risked igniting the second U.S. civil war by sending 1,000 American soldiers into a Southern city. The troops, with bayonets at the end of their rifles, provided protection for nine black students trying to get into Little Rock’s Central High School. Until the soldiers arrived, the black teenagers had been kept out by mobs and the Arkansas National Guard, in defiance of the Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling ending school segregation.

Here’s a web site dedicated to this episode of American history that provides some background:

Three years after the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision, which officially ended public-school segregation, a federal court ordered Little Rock to comply. On September 4, 1957, Governor Orval Faubus defied the court, calling in the Arkansas National Guard to prevent nine African American students–“The Little Rock Nine”–from entering the building. Ten days later in a meeting with President Eisenhower, Faubus agreed to use the National Guard to protect the African American teenagers, but on returning to Little Rock, he dismissed the troops, leaving the African American students exposed to an angry white mob. Within hours, the jeering, brick-throwing mob had beaten several reporters and smashed many of the school’s windows and doors. By noon, local police were forced to evacuate the nine students.

When Faubus did not restore order, President Eisenhower dispatched 101st Airborne Division paratroopers to Little Rock and put the Arkansas National Guard under federal command. By 3 a.m., soldiers surrounded the school, bayonets fixed.

Under federal protection, the “Little Rock Nine” finished out the school year. The following year, Faubus closed all the high schools, forcing the African American students to take correspondence courses or go to out-of-state schools. The school board reopened the schools in the fall of 1959, and despite more violence–for example, the bombing of one student’s house–four of the nine students returned, this time protected by local police.

This incident enflamed southern white segregationists. Since the end of Reconstruction in 1877, they’d had a free hand to oppress African Americans all they liked. Now the federal government was enforcing the civil rights of citizens of color, and the yahoos were outraged. This was a violation of states’ rights, they said. (And, frankly, I believe much libertarian antipathy toward “big government” was kick-started by the Little Rock showdown also.)

“States’ rights” wasn’t a new idea, of course. But it had a clear connection to segregation. In 1948, several southern Democrats bolted when the Democrats put an anti-segregation plank in the party platform. This splinter group formed the States’ Rights Democratic Party, whose slogan was “segregation forever.”

Surely any American in the 1950s and 1960s with a measurable IQ understood that “states’ rights” was a code word for “white supremacy.” Today you’d still have to be pretty thick not to get that, but we do seem to have a lot of thick people among us these days.

Anyway, the Democratic Party became increasingly split between the northern, mostly pro-civil rights Dems and the southern segregationist Dems. Lyndon Johnson’s endorsement of civil rights legislation, followed by his antipoverty programs, were the last straws for southern Democrats. Eventually several prominent segregationist Dems switched parties and became Republican, along with a majority of white voters. In the 1950s “solid South” referred to the fact that southern states voted as a block for Democrats. Now the southern states vote as a block for Republicans.

I realize most of you know this, but it still has to be spelled out for righties. They refuse to acknowledge this is what happened. Yes, 50 years ago the Republican Eisenhower supported civil rights, and the Democratic Faubus did not. That was before the Southern strategy, my dears. Things have changed a bit since.

One of the more pathetic attempts at denial comes from Jon Henke at Q and O. Reagan did not kick off his re-election campaign in Philadelphia, Mississippi, says Henke. He was at a fairground ten or twenty miles outside of Philadelphia, Mississippi.

Please. Reagan was in Mississippi, in the same county in which Andrew Goodman was murdered, and he said “I believe in states’ rights.” Reagan couldn’t have been more explicit if he’d said “I believe in Jim Crow.” Reagan may not have re-instated Jim Crow laws (as President, that was outside his authority), but then he campaigned against abortion, also, without bothering to follow up.

Herbert continues,

In 1981, during the first year of Mr. Reagan’s presidency, the late Lee Atwater gave an interview to a political science professor at Case Western Reserve University, explaining the evolution of the Southern strategy:

“You start out in 1954 by saying, ‘Nigger, nigger, nigger,’ †said Atwater. “By 1968, you can’t say ‘nigger’ — that hurts you. Backfires. So you say stuff like forced busing, states’ rights, and all that stuff. You’re getting so abstract now [that] you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things, and a byproduct of them is [that] blacks get hurt worse than whites.â€

To go back to an example I’ve used before in another context, check out Richard Nixon’s 1972 Republican Convention acceptance speech. Although it’s all in code, the first half of the speech is about race.

The first issue Nixon launched into was not Vietnam, but quotas. He was speaking out against Affirmative Action. He spoke of “millions who have been driven out of their home in the Democratic Party” — this was a nod to the old white supremacist Dixiecrats who were leaving the Democratic Party because of its stand in favor of civil rights (the famous Southern Strategy). McGovern had proposed a guaranteed minimum income for the nation’s poor that was widely regarded as radical and flaky and (in popular lore) amounted to taking tax money away from white people and giving it to blacks. Nixon warned that McGovern’s policies would raise taxes and also add millions of people to welfare roles — another racially charged issue. Then Nixon took on one of his favorite issues, crime. If you remember those years you’ll remember that Nixon was always going on about “lawnorder.” This was another issue with racial overtones, but it was also a swipe at the “permissiveness” of the counterculture and the more violent segments of the antiwar and Black Power movements.

Herbert continues,

In 1991, the first President Bush poked a finger in the eye of black America by selecting the egregious Clarence Thomas for the seat on the Supreme Court that had been held by the revered Thurgood Marshall. The fact that there is a rigid quota on the court, permitting one black and one black only to serve at a time, is itself racist.

Mr. Bush seemed to be saying, “All right, you want your black on the court? Boy, have I got one for you.â€

Republicans improperly threw black voters off the rolls in Florida in the contested presidential election of 2000, and sent Florida state troopers into the homes of black voters to intimidate them in 2004.

And righties wonder why African Americans tend to vote for Democrats. Well, actually, they don’t wonder. They have a Theory. African-Americans are being kept in a slave relationship with the Democratic Party, the theory goes. African Americans are being kept on the Democratic Party plantation. According to Francis Rice, chairman of the National Black Republican Association,

In order to break the Democrats’ stranglehold on the black vote and free black Americans from the Democrat Party’s economic plantation, we must shed the light of truth on the Democrats. We must demonstrate that the Democrat Party policies of socialism and dependency on government handouts offer the pathway to poverty, while Republican Party principles of hard work, personal responsibility, getting a good education and ownership of homes and small businesses offer the pathway to prosperity.

There’s a decent deconstruction of Rice at People for the American Way. And no, Martin Luther King was not a Republican.

The Freepers give us some nice elaboration on the “Democratic plantation” theory:

Democrats are seen as the party of proactive government. Blacks are disproportionately employed in government employment. ‘Nuff said. … Deterioration with black culture and breakdown of the family starting in the 60’s including high drug usage rate, high dropout rate, high illegitamcy rate, high incarceration rate, high welfare dependency rate. The more people behave irresponsibly and depend on the government, the more likely they will vote Democrat. … The democrats bought the votes of blacks with the massive “Great Society” spending programs that over proportionality took money from non black America and gave it to black America. We can argue that these programs destroyed the black family – but now they are entitlements and blacks will vote for anyone who will fund and expand them… How about the black minority is a surrogate action group for post holocast Jews. The blacks were assigned civil rights issues that would benefit the smaller minority Democrat Jews. … It goes back to the Johnson administration when he voted into law “The Great Society” meaning you could sit on your ass and collect welfare for life. This was specifically sold to inner-city blacks coming on the heals of then civil rights movement which was Republican led, I should add. … Because Democrats decided that they wanted to champion the Civil Rights movement and set out to show Blacks that they were victims and needed a lot of free handouts to “make it”. Human nature seems to gravitate towards those that want to give you something for nothing and to tell you that you can do no wrong because any wrong you do is someone else’s fault. The irony is, Democrats have effectively put many Blacks back into slavehood, and they embraced it willingly.

And on and on. You can count on the Freep to show us the naked truth of rightieness.

I’m not going to heap any praise on the Democratic Party, because frankly it hasn’t done as much as it could have to earn African American votes. I’d say it’s Republicans that persuade African Americans to vote for Democrats. Bob Herbert explains how.

The New York Times has dismantled the evil Times Select firewall (yay).

It’s also given Paul Krugman a blog, called “The Conscience of a Liberal.” Here’s the first post. It begins:

“I was born in 1953. Like the rest of my generation, I took the America I grew up in for granted — in fact, like many in my generation I railed against the very real injustices of our society, marched against the bombing of Cambodia, went door to door for liberal candidates. It’s only in retrospect that the political and economic environment of my youth stands revealed as a paradise lost, an exceptional episode in our nation’s history.”

That’s the opening paragraph of my new book, The Conscience of a Liberal. It’s a book about what has happened to the America I grew up in and why, a story that I argue revolves around the politics and economics of inequality.

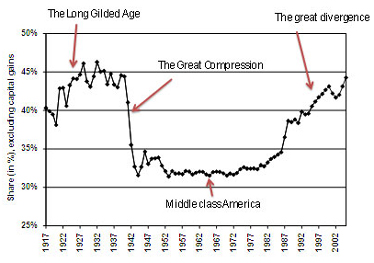

He provides a thumbnail review of the past ninety or so years of the U.S. economy, divided into four periods, as shown on this chart:

Krugman says,

The chart shows the share of the richest 10 percent of the American population in total income — an indicator that closely tracks many other measures of economic inequality — over the past 90 years, as estimated by the economists Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez. I’ve added labels indicating four key periods.

The four periods are the Long Gilded Age (which ended ca. 1937), the Great Compression (ca. 1937 to mid-1940s), Middle Class America (mid-1940s to late 1970s), and the Great Divergence (late 1970s to now).

I’ll get back to the Great Compression, but this is what Krugman says about the last couple of periods:

Middle class America: That’s the country I grew up in. It was a society without extremes of wealth or poverty, a society of broadly shared prosperity, partly because strong unions, a high minimum wage, and a progressive tax system helped limit inequality. It was also a society in which political bipartisanship meant something: in spite of all the turmoil of Vietnam and the civil rights movement, in spite of the sinister machinations of Nixon and his henchmen, it was an era in which Democrats and Republicans agreed on basic values and could cooperate across party lines.

The great divergence: Since the late 1970s the America I knew has unraveled. We’re no longer a middle-class society, in which the benefits of economic growth are widely shared: between 1979 and 2005 the real income of the median household rose only 13 percent, but the income of the richest 0.1% of Americans rose 296 percent.

Certainly, the Middle Class America period wasn’t perfect, especially since racial minorities were kept locked out. But if you’re as old as Krugman and I — I’ve got a couple of years on him, actually — you know that the American middle class ain’t what it used to be. Not even close. Relative share of wealth and, IMO, quality of life have declined in many ways. I see a whopping large chunk of American citizens struggling more and more frantically to maintain what they were brought up to think is a “normal” lifestyle.

But our ideas of “normal” came out of a period that Krugman calls “a paradise lost, an exceptional episode in our nation’s history.”

I’m going to skip Krugman for a moment and go to a Harold Meyerson column from last year (August 30, 2006).

Labor Day is almost upon us, and like some of my fellow graybeards, I can, if I concentrate, actually remember what it was that this holiday once celebrated. Something about America being the land of broadly shared prosperity. Something about America being the first nation in human history that had a middle-class majority, where parents had every reason to think their children would fare even better than they had….

…From 1947 through 1973, American productivity rose by a whopping 104 percent, and median family income rose by the very same 104 percent. More Americans bought homes and new cars and sent their kids to college than ever before. In ways more difficult to quantify, the mass prosperity fostered a generosity of spirit: The civil rights revolution and the Marshall Plan both emanated from an America in which most people were imbued with a sense of economic security.

That America is as dead as the dodo. Ours is the age of the Great Upward Redistribution. The median hourly wage for Americans has declined by 2 percent since 2003, though productivity has been rising handsomely. Last year, according to figures released just yesterday by the Census Bureau, wages for men declined by 1.8 percent and for women by 1.3 percent.

The increase of two-income families masked the inequality for a while; people with two incomes were able to maintain the same level of “normal” that one wage earner provided in earlier times. But now the two wager-earners are working longer hours, skipping vacations, and living from paycheck to paycheck. They are clinging to Middle Class-ness by their fingertips.

Back to Meyerson:

According to a report by Goldman Sachs economists, “the most important contributor to higher profit margins over the past five years has been a decline in labor’s share of national income.”…

…For those who profit from this redistribution, there’s something comforting in being able to attribute this shift to the vast, impersonal forces of globalization. The stagnant incomes of most Americans can be depicted as the inevitable outcome of events over which we have no control, like the shifting of tectonic plates.

Problem is, the declining power of the American workforce antedates the integration of China and India into the global labor pool by several decades. Since 1973 productivity gains have outpaced median family income by 3 to 1. Clearly, the war of American employers on unions, which began around that time, is also substantially responsible for the decoupling of increased corporate revenue from employees’ paychecks.

But finger a corporation for exploiting its workers and you’re trafficking in class warfare. Of late a number of my fellow pundits have charged that Democratic politicians concerned about the further expansion of Wal-Mart are simply pandering to unions. Wal-Mart offers low prices and jobs to economically depressed communities, they argue. What’s wrong with that?

Were that all that Wal-Mart did, of course, the answer would be “nothing.” But as business writer Barry Lynn demonstrated in a brilliant essay in the July issue of Harper’s, Wal-Mart also exploits its position as the biggest retailer in human history — 20 percent of all retail transactions in the United States take place at Wal-Marts, Lynn wrote — to drive down wages and benefits all across the economy. The living standards of supermarket workers have been diminished in the process, but Wal-Mart’s reach extends into manufacturing and shipping as well. Thousands of workers have been let go at Kraft, Lynn shows, due to the economies that Wal-Mart forced on the company. Of Wal-Mart’s 10 top suppliers in 1994, four have filed bankruptcies.

For the bottom 90 percent of the American workforce, work just doesn’t pay, or provide security, as it used to.

Devaluing labor is the very essence of our economy.

Krugman:

On the political side, you might have expected rising inequality to produce a populist backlash. Instead, however, the era of rising inequality has also been the era of “movement conservatism,” the term both supporters and opponents use for the highly cohesive set of interlocking institutions that brought Ronald Reagan and Newt Gingrich to power, and reached its culmination, taking control of all three branches of the federal government, under George W. Bush. (Yes, Virginia, there is a vast right-wing conspiracy.)

Because of movement conservative political dominance, taxes on the rich have fallen, and the holes in the safety net have gotten bigger, even as inequality has soared. And the rise of movement conservatism is also at the heart of the bitter partisanship that characterizes politics today.

I have a lot of thoughts as to why this happened, but those will have to wait for another post. For now I’ll just say that you probably have to be a geezer like me or Krugman to appreciate the difference between Then and Now. The Fall of the Middle Class happened gradually enough that it took some time before we realized that steadily increasing prosperity had been replaced by ceaseless struggling just to keep from sliding further. If the change from, say, the economy of 1967 to the economy of 2007 had happened over a five-year period there would have been rioting in the streets.

On the other hand, if your earliest memories are from after the 1960s, you might not see the difference. Righties — and I still say they are disproportionately Gen X-ers — get a little boost in their stock portfolios and think life is fine, but they’re not seeing the big picture.

In some ways, the conversation over whether inequality is being driven by impersonal, technical forces or government policy is neither here nor there (at least on a policy level — politically, people use it to justify inequality as something organic, inevitable, and even beautiful — like the tides). We live in a regulated economy governed by both public and private institutions, so there’s no such thing as “natural” forces. Even if superstar CEOs are taking home billions, they’re still reliant on our system of contracts, and limited liability, and stock market regulation. In other words, what public policy giveth, public policy can taketh away. Few doubt that we have the tools — using something called “the tax code” — to engage in some redistribution. The question is whether we have the will.

I don’t think the tax code is the only tool we have, but it’s a start.

Very briefly I want to go back to the Great Compression. It’s interesting to me that the Compression began abruptly about seven or eight years into the Great Depression, which seems to me is an argument that the Great Depression was not a cause of the Compression, as this blogger argues. No doubt myriad factors were involved, and if I had more time today I’d go back to see exactly what New Deal policies were in place by 1936 or so that might have helped the Compression along. Yes, the industrial buildup during World War II was a huge factor, but that was instigated and overseen by the federal government during the FDR Administration.

Today’s Paul Krugman column is a must read. Shorter version: We are all New Orleans now.

Today, much of the Gulf Coast remains in ruins. Less than half the federal money set aside for rebuilding, as opposed to emergency relief, has actually been spent, in part because the Bush administration refused to waive the requirement that local governments put up matching funds for recovery projects — an impossible burden for communities whose tax bases have literally been washed away.

On the other hand, generous investment tax breaks, supposedly designed to spur recovery in the disaster area, have been used to build luxury condominiums near the University of Alabama’s football stadium in Tuscaloosa, 200 miles inland.

But why should we be surprised by any of this? The Bush administration’s response to Hurricane Katrina — the mixture of neglect of those in need, obliviousness to their plight, and self-congratulation in the face of abject failure — has become standard operating procedure. These days, it’s Katrina all the time.

If you want to be worked into blubbering outrage, read Tim Shorrock’s “Hurricane Recovery, Republican Style” in Salon. Although tight-fisted with Louisiana, the Bushies have been more than generous to Mississippi and its Republican governor, former RNC chairman Haley Barbour. But distribution of the funds in Mississippi has favored the wealthy, and a large part of it is being used to build casinos and luxury condominiums while poor, devastated communities wait for help. And notice there’s little about this outrage in the mainstream media.

Krugman continues,

Consider the White House reaction to new Census data on income, poverty and health insurance. By any normal standard, this week’s report was a devastating indictment of the administration’s policies. After all, last year the administration insisted that the economy was booming — and whined that it wasn’t getting enough credit. What the data show, however, is that 2006, while a good year for the wealthy, brought only a slight decline in the poverty rate and a modest rise in median income, with most Americans still considerably worse off than they were before President Bush took office.

Most disturbing of all, the number of Americans without health insurance jumped. At this point, there are 47 million uninsured people in this country, 8.5 million more than there were in 2000. Mr. Bush may think that being uninsured is no big deal — “you just go to an emergency room” — but the reality is that if you’re uninsured every illness is a catastrophe, your own private Katrina.

Yet the White House press release on the report declared that President Bush was “pleased” with the new numbers. Heckuva job, economy!

Today E.J. Dionne wonders why the rising number of uninsured Americans isn’t getting more news coverage. “Why is it that the poor — and, for that matter, the struggling middle class, too — disappear in the media, barricaded behind our fixation on celebrity, our titillation with personal sin and public shame, our fascination with every detail of every divorce and affair of every movie star, rock idol and sports phenom?” he asks.

Poll after poll puts health care near the top of citizens’ concerns. But I’ve yet to see anything remotely resembling an intelligent discussion about the health care crisis in mass media. If the issue is addressed at all, it’s given a six-minute segment in which some well-paid partisans mouth talking points and demonstrate they are utterly out of touch with Americans’ real opinions and concerns.

Back to Professor Krugman:

The question is whether any of this will change when Mr. Bush leaves office.

There’s a powerful political faction in this country that’s determined to draw exactly the wrong lesson from the Katrina debacle — namely, that the government always fails when it attempts to help people in need, so it shouldn’t even try. “I don’t want the people who ran the Katrina cleanup to manage our health care system,” says Mitt Romney, as if the Bush administration’s practice of appointing incompetent cronies to key positions and refusing to hold them accountable no matter how badly they perform — did I mention that Mr. Chertoff still has his job? — were the way government always works.

And I’m not sure that faction is losing the argument. The thing about conservative governance is that it can succeed by failing: when conservative politicians mess up, they foster a cynicism about government that may actually help their cause.

This worries me, also. Younger people in particular (i.e., anyone born after 1970) can’t remember a time before the “government doesn’t work” meme took hold. My parents’ generation, whose ideas about government’s capabilities were shaped by FDR’s Hundred Days and World War II, generally trusted government. It was us Boomers who became cynical about government, and not without reason. But now that cynicism is paralyzing us.

Even as the health care crisis touches nearly everyone in the middle class, directly or indirectly, government and media continue to treat it as some little inconvenience for “the poor.” Being cut off from all but emergency care is considered a personal problem no doubt resulting from an individual’s bad choices. Just about every voice in Washington and mass media tells citizens that it’s wrong to expect government to make it possible to get decent health care. They should just suck it up and cut out trans fats. (See also “Let Them Eat Gold-Plated Cake.”)

But while ordinary Americans have bought the idea that government solutions are not for them, for the wealthy and well-connected government works just fine.

Of course, the Right cannot abide the thought of citizens using their own government to solve problems. Even though they mostly support the Republican Party, the Right doesn’t seem to grasp republican government. They think like 19th century imperialists who saw the “underclasses” as an intractable burden, and their “let it rot” attitude toward New Orleans is reminiscent of Britain’s treatment of Ireland during the Hunger.

Lurking behind much rhetoric about “big government” is Friedrich Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom, first published in 1944. Full disclosure: I haven’t read Hayek, although I’d be willing to bet not many of today’s wingnuts have read him, either. But I understand that his ideas had an enormous impact on people like Milton Friedman, Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. “Hayek’s central thesis is that all forms of collectivism lead logically and inevitably to tyranny,” says Wikipedia. For a synopsis I’m told is accurate, see the cartoon version.

Hayek’s first step, “war forces national planning” of the economy, was no doubt a swipe at Franklin Roosevelt’s War Production Board, which I notice did not lead to serfdom. But generally, says Hayek, planned economies lead to planned everything else, and pretty soon you’ve got a totalitarian government. Certainly the Soviet-style planned economy was accompanied by political oppression, and bread lines to boot. But I have never in my life met a fellow American who seriously proposed establishing a planned economy, in which government controls all production and distribution of income. And there’s a huge difference between a planned economy and citizens choosing, through their elected representatives, to establish a universal health care system.

And the biggest laugh of all is that righties, fleeing in hysteria from serfdom threatened by communist government, run headlong into the waiting arms of serfdom imposed by a corporatist government.

Professor Krugman concludes:

Future historians will, without doubt, see Katrina as a turning point. The question is whether it will be seen as the moment when America remembered the importance of good government, or the moment when neglect and obliviousness to the needs of others became the new American way.

I think it can be argued that America has been at this crossroads for a long time. Certainly “neglect and obliviousness to the needs of others” was the rule through all the years when white America was able to shut racial minorities out of equal opportunity, for example. But the truth is that as long as America had a big, strong and upwardly mobile middle class, the nation also grew stronger and, in fits and starts, wealthier. But now the rot has reached into the middle class, and if we don’t turn this trend around, America can look forward to long years of diminishment and decline.